art.wikisort.org - Artist

Christiana Mary Demain Hammond (6 August 1860 – 11 May 1900) was an English painter and illustrator. She was a member of the Cranford School of illustration, and illustrated reissues of classic English texts from the 19th century. Her illustrations were frequently found in Cassell's Magazine, the Quiver, and St. Paul's.[1] She exhibited occasionally at the Royal Academy and Royal Institute of Painters in Watercolours.[note 1]

Christiana Mary Demain Hammond | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 6 August 1860 Camberwell, London, England |

| Died | 11 May 1900 (aged 39) 2 St. Paul's Studio, Talgath Road, West Kensington, London, England |

| Nationality | English |

| Other names | Chris Hammond |

| Occupation | Artist and illustrator |

| Years active | 1886 – 1900 |

| Known for | Illustrating the works of Jane Austen, Maria Edgeworth and other classics |

Early life

Hammond Mary Demain Hammond was born in Coldharbour Lane, Brixton, London on 6 August 1860,"[3] and baptised on 16 September 1860.[4] She was not named on her birth registration, but simply registered as a female child. Her parents were Horatio Demain Hammond (c. 1833 – 11 March 1900),[5] a bankers clerk, and Eliza Wood (baptised 21 June 1836 – first quarter of 1882), who had married in St. George's, Bloomsbury, London on 5 May 1858.[6]

The couple had three children, all of whom were artists:

- Christiana Mary Demain (1860 – 11 May 1900)

- Gertrude Ellen Demain RI (baptised 6 July 1862 – 21 July 1951).[7][8] Gertrude and Christiana trained together, first at the Lambeth School of Art and then at the Royal Academy Schools. She was a painter and illustrator like Hammond. Gertrude was a prolific illustrator of books, including children's books and the retelling of historical stories. Gertrude married Henry Going McMurdie (c. 1860 – 28 November 1948)[9] in Fulham, London on 14 June 1898[10] and the couple lived with Hammond at 2 St. Paul's Studios, in what is now Talgath Road, Kensington.[note 2][11]

- Percy Edward Demain (6 December 1865 – 3 April 1946)[12][13] was described himself as a stained-glass artist in the 1901 census and as a decorative artist in 1911 and 1939.[12] In 1906 he was working as an artist for Crittall Manufacturing Company, famous for their involvement in the Art-Deco movement, both as suppliers of steel windows used in art deco buildings, and for commissioning buildings in the art deco style.[14] He was described as a Poster Artist in 1907, suggesting that he was involved in advertising for Crittall.[15] Percy married Martha Cantwell in Lambeth in the third quarter of 1904.[16] The couple had at least one son, Seymour Edward Demain (baptised 7 July 1905 – 15 October 1948)[17][18]

Christiana was the only one of her siblings who did not marry.

Education

Hammond received her first training in drawing from her Governess, and then attended the Lambeth School of Art with her sister Gertrude in 1879.[19]: 136 At the Lambeth School, Hammond won the Cressy for the best sketch on a particular subject, a competition open to all the students at the school, with the award made by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema.[20]

Hammond and her sister both won scholarships for three years tuition at the Royal Academy Schools, where they began in 1889.[19]: 136 Here, Hammond distinguished herself by passing through the various schools almost as rapidly as was possible. However, she was not eligible for a second three year scholarship as, although she had passed all her exams, she had missed many lectures due to illness, and a good attendance record was a requirement for a further scholarship. Thus her artistic education ended three year earlier than she would have liked. It was this foreshortening of her education that led her to concentrate on pen and ink work rather than oil painting.[20]

Works

Hammond painted, and exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1886, 1891, 1892, 1893, and 1894, and at the Royal Society of Painters in Watercolours in 1886 and 1895.[21] While still a student at the Royal Academy Schools she came to the attention of James Barr, editor of the Detroit Free Press and Henry Reichardt, art-editor of Pick-Me-Up, both of whom gave her commissions. Hammond also contributed to the first issue of Reichardt's new illustrated weekly St. Paul's in 1884. After this first appearance of her work in St. Paul's she was approached not only by publishers such as Macmillan and Allen, but also by Sir William Ingram, the proprietor of both the Illustrated London News and The Sketch. From then on she was turning away work, as she was offered more commissions than she could complete.[20]

She was also published in Cassell's Magazine, The Quiver, The English Illustrated Magazine,[note 3][22] The Queen,[21] Pall Mall Magazine, Pearson’s Magazine, The Idler,[1] Madame,[23]: 77 Good Words,[23]: 133 The Ludgate Monthly,[23]: 151 and The Temple Magazine[23]: 180

Hammond is regarded as a member of the Cranford School along with the C. E. Brock, H. M. Brock, Fred Pegram, F. H. Townsend and the inaugurator Hugh Thomson. The school was strictly speaking a shared style, as the individual artists had no particular relationship with each other. It was a style which celebrated a sentimental, pre-industrial notion of ‘old England’.[1]

Books illustrated by Hammond

The following list is based on the list presented in the Argosy obituary.[20] Most of the Hammond's work were for posthumous editions. However, in three cases she illustrated first editions.

| Serial | Year | Author | Title | Publisher | Edition |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1895 | Maria Edgeworth | Castle Rackrent | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 2 | 1895 | Maria Edgeworth | The Absentee | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 3 | 1895 | Maria Edgeworth | Popular Tales | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 4 | 1895 | Jean-François Marmontel | Moral Tales | London: George Allen | Posthumous |

| 5 | 1895 | Samuel Richardson | Sir Charles Grandison | London: George Allen | Posthumous |

| 6 | 1896 | Maria Edgeworth | Helen | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 7 | 1896 | Maria Edgeworth | Belinda | London:Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 8 | 1896 | Oliver Goldsmith | Comedies | London: George Allen | Posthumous |

| 9 | 1897 | Maria Edgeworth | The Parent's Assistant | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 10 | 1897 | William Makepeace Thackeray | The History of Henry Esmond | London: Service & Paton | Posthumous |

| 11 | 1897 | William Makepeace Thackeray | Pendennis | London: Service & Paton | Posthumous |

| 12 | 1897 | R. D. Blackmore | Dariel | London: Blackwood | First Edition |

| 13 | 1898 | William Makepeace Thackeray | Vanity Fair | London: Service & Paton | Posthumous |

| 14 | 1898 | William Makepeace Thackeray | The Newcomes | London: Service & Paton | Posthumous |

| 15 | 1898 | Robert Bulwer-Lytton | The Caxtons | London: Service & Paton | Posthumous |

| 16 | 1898 | Jane Austen | Emma | London: George Allen | Posthumous |

| 17 | 1898 | Mary Catherine Rowsell | The Boys of Fairmead | London: Warne | First Edition |

| 18 | 1899 | Jane Austen | Sense and Sensibility | London: George Allen | Posthumous |

| 19 | 1899 | Mrs. Craik | John Halifax, Gentleman | London: E. Nisbet | Posthumous |

| 20 | 1899 | Oliver Vernon Caine | In the Year of Waterloo | London: E. Nisbet | First Edition |

| 21 | 1899 | Maria Edgeworth | Lazy Laurence, and Other Stories | London: Macmillan | Posthumous |

| 22 | 1899 | Mrs. Gaskell | Cranford | Glasgow: Gresham Publishing Co. | Posthumous |

| 23 | 1899 | Mrs. Gaskell | Mary Barton | Glasgow: Gresham Publishing Co. | Posthumous |

| 24 | 1899 | Jane Austen | Pride and Prejudice | Glasgow: Gresham Publishing Co. | Posthumous |

Example of illustrations by Hammond

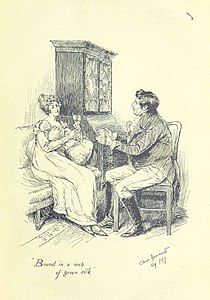

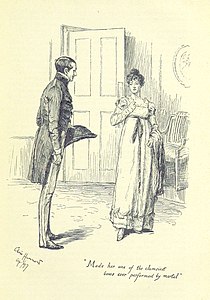

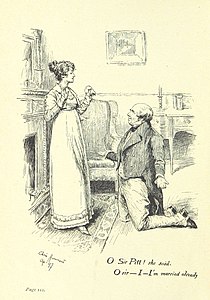

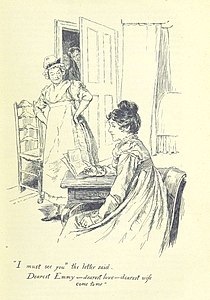

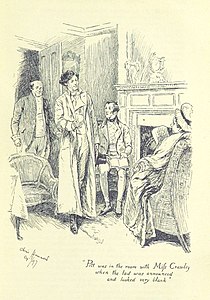

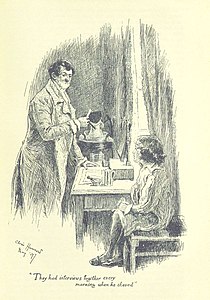

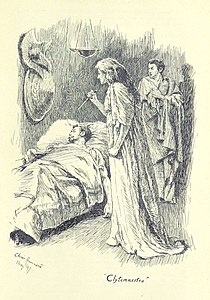

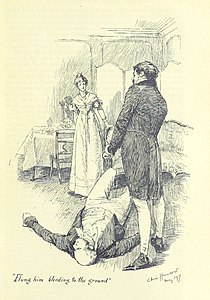

Illustration by Hammond for the 1898 Service & Patton reissue of Vanity Fair by Thackeray.

- Page 029

- Page 037

- Page 082

- Page 112

- Page 141

- Page 167

- Page 236

- Page 272

- Page 304

- Page 336

- Page 373

- Page 396

- Page 413

- Page 430

- Page 472

- Page 557

Death

Hammond died unexpectedly in the house she shared with her sister and brother-in-law on 11 May 1900, aged 39.[24] Her father has died only two months previously. Her estate was valued at £2,198 2s. Her brother Percy acted as her executor.[24]

Assessment

Forman in her Argosy obituary stated that no competent critic would deny her a place among the foremost six of her contemporaries, and that others, of no less competence, would unhesitatingly rank her among the foremost three. and that Fancy, delicacy, vigour, variety, subtlety of characterisation, distinction in both conception and execution were all in rich measure at Miss Hammond's command.[20]

Thorpe noted that Hammond's delicate and charming pen-drawings were very popular and that she had a long list of books to her credit.[23]: 225 However, he also considered that many of her figures – particularly the women – were spoilt by disproportionately small heads, and her sister was the more skilful draftsman. Hammond and her sister in the 1890's were at that time certainly the most distinguished members of their sex in the field of illustration.[23]: 89 Peppin concurs with Thorpe's assessment that Gertrude was the better draftsman.[19]: 136

Houfe notes that Hammond's penwork is rather free and she excels in costume subjects in a style not unlike that of the Brocks' eighteenth century pastiches.[25]: 331 [note 4] Loosey notes that Hammond was the first identifiably female illustrator of Jane Austen’s novels, illustrating three Austen titles for two publishers. And that when compared with other members of the Cranford School, Hammond’s Austen illustrations are on the whole more serious, less whimsical, and more visually surprising than Thomson’s or the Brocks’.[26] Southam calls Hammond the finest artist of this period and states that her decisive and characterized pen-and-ink drawings are neither whimsical nor over decorative.[27]

Cooke states that Hammond's contribution to the Cranford School's escapist discourse of a sentimental pre-industrial Old England was simple but effective. Though representing her characters with historical exactitude, her main focus is on small nuances of facial expression and gesture. This makes her an ideal illustrator for Jane Austen. Cooke summarised by saying that Catering for a large bourgeois audience, her refined and perceptive illustrations had a wide currency, only supplanted by the growing taste for the radicalism of English Art Nouveau.[1]

Notes

- Hammond exhibited as follows: six works at the Royal Academy, two works at the Royal Society of British Artists, two works at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours, and one work at the Royal Institute of Oil Painters.[2]

- This was part of a terrace of eight house designed by Frederick Wheeler FRIBA (1853 – 1931) as artists' studios, with a large lantern light on front of the house on the second floor. The studios were used as the settings for a murder in J. K. Rowlings The Silkworm, and featured in the BBC adaptation of the novel. One of the eight studios was listed for sale for £2,000,000 in 2018

- The English Illustrated Magazine continued to use her illustrations after her death, the last appearing in December 1912. The final issue of the magazine was in August 1913.

- Houfe not only gets Hammond's name wrong, calling her Christine rather than Christiana, but also has her alive and active ten years after her death when he describes here as fl. 1886-1910.

References

- Cooke, Simon (9 April 2016). "Christiana Mary Demain 'Chris' Hammond (1860–1900), an illustrator of the '90s". The Victorian Web: literature, history, & culture in the age of Victoria. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Johnson, J.; Greutzner, A. (8 June 1905). The Dictionary of British Artists 1880-1940. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. p. 225.

- "No 153: Unnamed Girl to Horatio Demain Hammond and Eliza Mary Hammond (formerly Wood)". 1860 Births in the District of Brixton. London: General Register Office. 1860.

- London Metropopolitan Archives. "Baptisms solemnised in the parish of St. Giles, Camberwell, in the county of Surrey in the year 1860". London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917. London: London Metropolitan Archives. p. 320.

- "Wills and Probate 1858-1996: Search for Surname Hammond and Year of Death 1900". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Marriages". Kentish Gazette (Tuesday 11 May 1858): 5. 11 May 1858.

- London Metropopolitan Archives. "Baptisms solemnised in the parish of St. Giles, Camberwell, in the county of Surrey in the year 1862: Gertrude Ellen Demain Hammond". London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1917. London: London Metropolitan Archives. p. 409.

- "Wills and Probate 1858-1996: Search for Surname McMurdie and Year of Death 1952". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "Wills and Probate 1858-1996: Search for Surname McMurdie and Year of Death 1949". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- London Metropopolitan Archives (14 June 1898). "Marriage Solemnized at St. Andrew's Church in the parish of Fulham in the county of London: Henry Going McMurdie". London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932. London: London Metropolitan Archives. p. 289.

- Denham, Jess (18 August 2018). "Redbrick relic in west London:Arts & Crafts house made famous in JK Rowling's crime fiction novel The Silkworm listed for sale". Evening Standard Homes & Property. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- National Archives (29 September 1939). 1939 Register; Reference: RG 101/888A: E.D. BQBN. Kew: National Archives.

- "Wills and Probate 1858-1996: Search for Surname Hammond and Year of Death 1946". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Elain Harwood (12 December 2019). Art Deco Britain: Buildings of the interwar years. Pavilion Books. pp. 45–. ISBN 978-1-84994-653-7.

- "An Eatanswill Statue". London Daily News (Tuesday 04 June 1907): 11. 4 June 1907.

- "Index entry". FreeBMD. ONS. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Surrey History Centre (2015). "Baptisms solemnised in the parish of Kew, in the county of Surrey in the Year One Thousand Nine Hundred and Five: Seymour Edward Demain Hammond". Surrey Church of England Parish Registers: 18907-1917. Woking: Surrey History Centre. p. 44.

- "Wills and Probate 1858-1996: Search for Surname Hammond and Year of Death 1948". Find a Will Service. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Peppin, Bridget; Micklethwait, Lucy (1984). Book Illustrators of the Twentieth Century. London: John Murray. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Forman, Alfred (122). "Chris Hammond - In Memorium". pp. 343–350. hdl:2027/uiug.30112042708948. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- A. & C. Black Ltd. (1967). "Hammond, Chris, painter and black and white artist". Who Was Who: A Companion to Who's Who Containing the Biographies of Those Who Died During the Period 1897-1915. Vol. I: 1897-1915. London: Adam and Charles Black. p. 311. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- "The Lovers: From a Drawing by Chris Hammond". The English Illustrated Magazine (4719): 232. 1912. hdl:2027/mdp.39015056060158. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

- Thorpe, James (1935). English Illustration: The Nineties. London: Faber and Faber.

- "Death Of Miss C. M. D. Hammond". Westminster Gazette (Monday 14 May 1900): 10. 14 May 1900.

- Houfe, Simon (1978). Dictionary of British Book Illustrators and Caricaturists, 1800-1914. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors' Club. Retrieved 17 June 2020.

- Loosey, Devoney (2017). "The Golden Age for Illustrated Austen: From Peacocks to Photoplays". The Making of Jane Austen: With a new Afterword. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Southam, Brian (2 January 2009). "Texts and Editions". In Tuite, Clara; Johnson, Claudia L. (eds.). A Companion to Jane Austen. Chichester, West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 51–60. doi:10.1002/9781444305968. ISBN 978-1405149099. Retrieved 18 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christine M. Demain Hammond. |

- St Paul's Studios where Hammond worked and died, on Google Street View.

- Books illustrated by Hammond online at the British Library.

- Books illustrated by Hammond online at the Hathi Trust

- Works by Christiana Mary Demain Hammond at Project Gutenberg

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии