art.wikisort.org - Artist

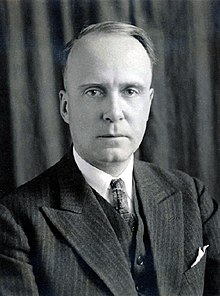

Kurt von Holleben (7 March 1894 – 14 January 1947) was a German chemist working for Agfa-Gevaert Technical-Scientific Laboratory as the head of the colour screen research group, overseeing development of Additive color screens (kornraster) for the Agfa-Farbenplatte glass plates (1916), and film based Agfacolor (1932) and Agfacolor Ultra (1934) ranges.

Early life

Albert Julius Ludwig Kurt von Holleben was born in Berlin, the only child of Auguste Marie Elisabeth (Wrede) (13 September 1868 – 7 October 1951) and Captain Curt Emil Ludwig von Holleben (5 April 1862 – 17 February 1910) of the Prussian Army 2nd Guard Regiment of Foot. His maternal grandfather was Wilhelm August Julius Wrede (23 January 1822 – 28 December 1895) the wealthy banker, sugar beet and spirits producer who owned the Schloss Britz (Britz castle) in Berlin. His paternal grandfather Albert Hermann Ludwig von Holleben (24 April 1835 – 1 January 1906) was a military historian, writer and Lieutenant General in the Prussian army.

His early schooling was in Wiesbaden and following that, the Dreikönigschule grammar school in Dresden.[1] Following the death of his father in 1910, his mother married Kurt Freiherr von Brandenstein (18 August 1870 – 4 June 1939), an up-and-coming lawyer and financier who would go on to become a privy councillor to the Saxon Ministry of Finance.[2]

Holleben graduated at Easter of 1913 and then went to Heidelberg University to study Law.

Military service 1914 - 1918

In August 1914, he enrolled in the Imperial Volunteer Automobile Corps.[1] These were civilians under contract, who in times of war would, with their private automobiles, form a transport unit for the staff officers. The owner/driver wore the corps uniform with Lieutenant rank epaulets; they were teamed with a mechanic who would wear a Sergeant's uniform. Within a year he transferred to the Saxon Army 1st Field Artillery Regiment No. 12 where he received officer training around 1917. In March 1918 he is listed as a Lieutenant (Leutnant) with Battery No. 7, and July 1918 as ordnance officer on the Regimental staff. He was demobilised to the army reserve in January 1919.[3][4]

Awards 1914-1918

Iron Cross 2nd Class, Iron Cross 1st Class, Friedrich-August Cross (class unknown), Albert Order 2nd Class (grade unknown).[5]

University education

Following demobilisation, he resumed his studies, though this time it was to study Chemistry at the Dresden University of Technology. Holleben achieved good marks for his preliminary examination in October 1920.[1]

One of the lecturers was Robert Luther (2 January 1868 – 17 April 1945) who had gained worldwide recognition for his lectures on the chemistry of photography and was someone with many contacts within the photographic industry; in 1909 the American photographer Imogen Cunningham came to Dresden to study under him.

Luther was the supervisor for Holleben's dissertation on “Drying of Gelatine” (Die Trocknung der Gelantine) for which he was awarded his Diplom-Ingenieur (Dipl.-Ing) in July 1922.[1]

Holleben's doctorate referees were Luther and Alfred Lottermoser (17 July 1870 – 27 April 1945) known for his work on colloid chemistry (the science behind the Agfacolour colour screen). His thesis was “On the induced oxidation of dyes” (Über die induzierte Oxydation von Farbstoffen) for which he was awarded his certificate 16 July 1924.[1]

Agfacolor development

Agfa had manufactured colour photographic glass plates since 1916; unlike the rival Autochrome process (which was launched in 1907) which used grains of potato starch, dyed in the three primary colours, to form the colour screen (or reseau), Agfa used an emulsion in which were suspended particles of resin dyed in primary colours (Kornraster). Agfa had acquired the patent for this process in 1910 from the Danish patent holder J. H. Christensen.

He joined Agfa at their Berlin-Treptow site on 1 May 1925,[6] and by 1926 he was head of the colour screen research group, overseeing development and production of Agfa-Farbenplatte colour glass plates. Following problems with the colour rendering of both green and blue, he changed the production to use alternative dyes and recommended using a Rapid Filter Yellow filter instead of a Tartrazine Yellow filter to improve blue rendition. Christensen continued the work begun by Holleben and in 1927 he proposed a new formulation and a switch from basic dyes to acidic dyes[7]

In 1928, plans were being drawn up to move the photographic production from Berlin-Treptow to its facility at Wolfen. Holleben was instrumental in the move; in 1930 he decided which buildings at Wolfen could be converted for production; in 1932 he was involved in discussions on how the move could be achieved without stopping production at Berlin-Treptow whilst still providing a continuous supply to customers. Holleben and the senior staff moved to Wolfen that month and were structurally integrated into the technical laboratories, and therefore subordinated to Dr. Wilmanns (the head of the Technical-Scientific Laboratory in Wolfen).[7]

In Wolfen, development continued on improving the colour screen sensitivity and shrinking the grain size to allow the development of the next generation of products. Agfacolor, an additive colour film on a nitrocellulose film base producing a positive image was released in 1932, and in 1934 they released Agfacolor Ultra a faster film version of its predecessor, also on a nitrocellulose film base, which was later changed to a safer acetylcellulose film base.

In 1936, colour screens were made redundant when Agfa developed the ground-breaking Agfacolor Nue process. This was a multi-layer colour reversal film with the colour couplers incorporated into three separate emulsion layers coated onto a single 'support' that could be processed in a single colour developer (it was a rival to the Kodachrome reversal film released in 1935). As a result, work on the work on raster screen plates and films reduced; he therefore also worked in the X-ray film factory.[6]

Holleben was part of the research team trialing the new film at the Garmisch-Partenkirchen 1936 Winter Olympics, where he photographed much of the event[8][9] (the film was not yet fast enough to capture live action).

As the dominance of the multi-layer colour film increased, he was by 1939 working in the test centre, and no longer involved in research.[6]

Patents

Professor Luther and Holleben were jointly awarded a patent (396,485)[10] on 8 May 1923 for a “Process for forming direct and reverse dye images”. This work was relevant to the Gasparcolor process and was quoted by Dr Béla Gáspár in his 1934 American patent (1,985,344) for a “Method of producing multicolour photographs and cinematograph pictures”.[11]

Holleben was awarded German patent number 545,745[12] on 4 March 1932 titled "Unexposed and undeveloped colored layers for photographic purposes".

Holleben and Dr Wilhelm Schneider (31 December 1900 – 2 August 1980) were awarded German patent number 2724[13] on 10 January 1936 titled "Process for producing color images with sound track".

Holleben, and a Wolfen colleague Wolf Rodenbacker, were awarded US patent number 2,086,930[14] on 13 July 1937 titled "Cassette for photographic films".

Holleben was awarded German patent number 762,767[15] on 9 July 1941 titled "Photographic tone separation process".

Military service 1939 – 1945

Following several absences from Agfa to attend military exercises, he was finally drafted into the military on 10 August 1939. He joined a Flak Regiment (Reserve-Flak-Abteilung 132) with the rank of Second Lieutenant. He was quickly promoted First Lieutenant and became a battery commander with the rank of Captain. In May 1940 he transferred to the Luftwaffe High Command Personnel Department at the Air Ministry (Reichsluftfahrtministerium) in Berlin, where he performed administrative work in the Officers Office. He was promoted Major and in May 1942 transferred to Leipzig as a Military District Officer at the Leipzig Replacement Army headquarters (Wehrersatzinspektion) sub-district command (Wehrbezirkskommando) Leipzig I which was responsible for the "conscription, training and replacement of personnel including control of mobilization policies and the actual call-up and induction of men; all types of military training, including the selection and schooling of officers and non-commissioned officers; the dispatch of personnel replacements to field units in response to their requisitions; and the organization of new units".[16] From 1945 to early 1946 he was held in an American Continental Central Prisoners of War Enclosure in North East France.[17]

Opposition to race laws

Although he had become a member of the Nazi Party when membership reopened in May 1937 (membership number 4945340) he had Jewish friends and an act of open defiance resulted in him being tried in a Nazi Party Court (Volksgerichtshof). He also suffered the disapproval of some colleagues at Agfa for his support of a young Jewish chemist Dr Fritz Luft who managed to escape to Argentina in 1938.[18] He was prevented from giving lectures on colour photography in Bitterfeld because of his views.[19]

Personal life

Holleben married Marie-Therese Henriette Margit Stark (25 May 1898 - ) on 20 August 1922[6] they were divorced on 14 November 1927 (in 1929 she married Generalleutnant Karl Rübel). Holleben had a foster son Herbert Meinecke (22 August 1916 – 20 October 2011).

Death

Following his release from American captivity in March 1946, he wrote to Agfa from Marburg in the hope of returning to work, but the Bitterfeld-Wolfen site was now in Soviet occupied territory making that impossible. Holleben died in Marburg on 14 January 1947 of spinal poliomyelitis.[6]

Legacy

In 1935, Holleben wrote a book on how to use Agfacolour films (Farbenfotografie mit Agfacolor-Ultra-Filmen und Agfacolor-Platten published by Heering of Harzburg).

The Handbuch der Medzizinischen Radiologie 1967, refers to (an untraced) "VON HOLLEBEN, K,: A method for checking the sharpness of the Rontgen films, applied to the Agfa-Accurata film test. Rontgen practice, 7: 558, 1935"

Holleben had access to as many photographic plates as he wished and photographed his extensive travels throughout Germany, Europe, Scandinavia and North Africa. He left a photographic archive of some six hundred 9x12 cm Agfa-Farbenplatte glass plates covering the period 1924 to 1939, and several hundred slides covering the period 1932 to 1940, which are now in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

References

- Biographisches Lexikon der frühen Promovenden der TU Dresden (1900–1945), accessed 28 June 2020

- Biographical details for Kurt Friedrich August Freiherr von Brandenstein, accessed 28 June 2020

- Outline of the history of the 1st Field Artillery Regiment No. 12, accessed 28 June 2020

- The military archive in Freiburg (Bundesarchiv-Abt. Militärarchiv) have no military records for Kurt, or his father, they were lost in bombing raids on Dresden, and Potsdam, during WW2

- Fragebogen - HHStAW_520--27_nr_18494

- Kurt von Holleben personnel file, Wolfen Museum of Industry and Film, Bunsenstrasse 4, D 06766 Wolfen or 06766 Wolfen, Germany.

- Die Filmfabrik Wolfen Aus der Geschichte, Heft 2, Die Pioniere des Wolfener Farbfilms

- Das alte Berlin in Farbe, Wartberg Verlag, 2019 pages 4, 43, 78 & 81

- Führerauftrag Monumentalmalerei: Eine Fotokampagne 1943-1945, Böhlau, 2006, page 50

- Process for forming direct and reverse dye images, accessed 1 August 2020

- Patent method of producing multicolour photographs and cinematograph pictures, accessed 28 June 2020

- Unexposed and undeveloped colored layers for photographic purposes, accessed 1 August 2020

- Process for producing color images with sound track, accessed 1 August 2020

- Cassette for photographic films, accessed 1 August 2020

- Photographic tone separation process, accessed 1 August 2020

- Axis History: The German Replacement Army, accessed 6 September 2020

- Bundesarchiv Gesch.-Z.: PA 2 2020/A-7110

- Letter from Prof. Dr. John Eggert - HHStAW_520--27_nr_18494

- Letter from Dr. E, Rolle - HHStAW_520--27_nr_18494

This article needs additional or more specific categories. (July 2020) |

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии