art.wikisort.org - Artist

Leopold Blaschka (27 May 1822 – 3 July 1895) and his son Rudolf Blaschka (17 June 1857 – 1 May 1939) were glass artists from Dresden, Germany, native to the Bohemian (Czech)–German borderland, and known for the production of biological models such as the glass sea creatures and Harvard University's Glass Flowers.

This article contains wording that promotes the subject in a subjective manner without imparting real information. (November 2017) |

Leopold Blaschka | |

|---|---|

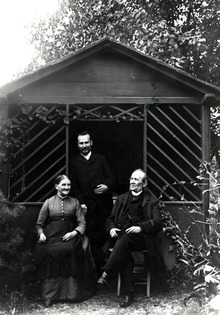

Rudolf (standing), Caroline, and Leopold Blaschka in the garden of their Dresden home | |

| Born | May 27, 1822 Český Dub, Bohemia |

| Died | July 3, 1895 (aged 73) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Glass artist |

| Notable work | Glass Flowers and Glass sea creatures |

| Spouse(s) | Caroline Zimmermann, Caroline Riegel |

Rudolf Blaschka | |

|---|---|

| Born | June 17, 1857 |

| Died | May 1, 1939 (aged 81) |

| Nationality | German |

| Known for | Glass artist |

| Notable work | Glass Flowers |

| Spouse | Frieda |

Family background

The Blaschka family traces its roots to Josefův Důl (Josefsthal) in the Jizera Mountains, Bohemia, a region known for processing glass, metals, and gems[1] and members of the family had worked in Venice,[2] Bohemia, and Germany.[3][4] Leopold referred to this history in an 1889 letter to Mary Lee Ware:

Many people think that we have some secret apparatus by which we can squeeze glass suddenly into these forms, but it is not so. We have the touch.[5] My son Rudolf has more than I have, because he is my son, and the touch increases in every generation. The only way to become a glass modeler of skill, I have often said to people, is to get a good great-grandfather who loved glass; then he is to have a son with like tastes; he is to be your grandfather. He in turn will have a son who must, as your father, be passionately fond of glass. You, as his son, can then try your hand, and it is your own fault if you do not succeed. But, if you do not have such ancestors, it is not your fault. My grandfather was the most widely known glassworker in Bohemia.[6][7]

Born in Český Dub, Bohemia, and one of Joseph Blaschke's three sons,[4][8] Leopold was apprenticed to a goldsmith and gemcutter in Turnov, a town in the Liberec Region of today's Czech Republic.[8] He then joined the family business, which produced glass ornaments and glass eyes.[2] He developed a technique which he termed "glass-spinning", which permitted the construction of highly precise and detailed works in glass. He also Latinised his family name to "Blaschka", and began to focus the business on the manufacture of glass eyes.[1]

Leopold married Caroline Zimmermann in 1846 and within four years their son Josef Augustin Blaschka was born.[8] Caroline and Josef died of cholera in 1850, and a year later his father died. Heartbroken, Leopold "sought consolation in the natural world, sketching the plants in the countryside around his home."[9][8]

Glass marine invertebrates

In 1853, Leopold traveled to the United States. En route the ship was delayed at sea for two weeks by lack of wind.[10] During this time Leopold studied and sketched local marine invertebrate, intrigued by the glass-like transparency of their bodies.[1] He wrote:

It is a beautiful night in May. Hopefully, we look out over the darkness of the sea, which is as smooth as a mirror; there emerges all around in various places a flashlike bundle of light beams, as if it is surrounded by thousands of sparks, that form true bundles of fire and of other bright lighting spots, and the seemingly mirrored stars. There emerges close before us a small spot in a sharp greenish light, which becomes ever larger and larger and finally becomes a bright shining sunlike figure.[10]

On return to Dresden, Leopold focused on his family business, producing glass eyes, costume ornaments, lab equipment, and other such fancy goods and specialty items that a master lampworker was responsible for.[11] He married Caroline Riegel in 1854.[8] He used his free time to create glass models of plants, as opposed to invertebrates. This would become a base for the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants (otherwise known as the Glass Flowers) many years later, but during this time Blaschka did not make any money producing the models.[11] Blaschka's models eventually attracted the attention of Prince Camille de Rohan, who arranged to meet with Leopold at Sychrov Castle in 1857, the year that the Leopold and Caroline's son Rudolf was born.[8] A naturalist himself, the Prince commissioned Leopold to craft 100 glass orchids for his private collection [2] and, impressed by Leopold's work, in 1862, "the prince exhibited about 100 models of orchids and other exotic plants, which he displayed on two artificial tree trunks in his palace in Prague,"[10][8] which brought the skill of the Blaschkas to the attention of Professor Ludwig Reichenbach.[12]

The director of the natural history museum in Dresden, Prof. Reichenbach, was enchanted by the botanical models and positive that Leopold held the key to ending his own inability to properly showcase marine invertebrates; in the 19th century the only practiced method of showcasing marine invertebrates was to take a live specimen and place it in a sealed jar of alcohol.[13] This killed the specimen, and due to time and their lack of hard parts, eventually rendered the specimens into little more than colorless floating blobs of jelly. The Dresden museum director desired specifically 3D colored models of marine invertebrates that were both lifelike and able to stand the test of time. [11] In 1863,[1] Reichenbach convinced and commissioned Leopold to produce twelve model sea anemones.[2][12][14] These marine models, hailed as "an artistic marvel in the field of science and a scientific marvel in the field of art,"[15] were a great improvement on previous methods of presenting such creatures: drawings, pressing, photographs and papier-mâché or wax models.[1]

Knowing this and thrilled with his newly acquired set of glass sea creatures, Reichenbach advised Leopold to drop his current and generations long family business of glass fancy goods and the like in favor of selling glass marine invertebrates to museums, aquaria, universities, and private collectors[1][2] - advice which prompted the swiftly and highly lucrative mail-order business that followed. Indeed, "the world had never seen anything quite like the beautiful, scientifically accurate Blaschka models"[16] and yet they were available via so common a means as via mail-order per one's local card catalog. Museums and universities began purchasing them en masse to put on display much as Prof. Reichenbach had - natural history museum directors across the world had the same issue showcasing marine invertebrates.[10] In short, Blaschkas Glass sea creature mail-order enterprise succeeded for two reasons: there was a huge and global demand, and they were the only and best glass artists capable of crafting literally scientifically flawless models. Initially the designs for these were based on drawings in books, but Leopold was soon able to use his earlier drawings to produce highly detailed models of other species,[1] and his reputation quickly spread; the task additionally furthering the training of his son and apprentice (and eventual successor), Rudolf Blaschka.[2] A year after the success of the glass sea anemones, the family moved to Dresden to give young Rudolf better educational opportunities.[1]

Belgium

In 1886, Edouard Van Beneden, founder of the Institute of Zoology, ordered 77 Blaschka models in order to illustrate zoology lessons. Some of these models are still on display at TréZOOr, in the Aquarium-Muséum in Liège.[17][citation needed]

Contact with Harvard

Around 1880, Rudolf began assisting his father with the models. In that year, they produced 131 Glass sea creature models for the Boston Society of Natural History Museum (now the Museum of Science). These models, along with the ones purchased by Harvard's Museum of Comparative Zoology, were seen by Professor George Lincoln Goodale, who was in the process of setting up the Harvard Botanical Museum. In 1886, the Blaschkas were approached by Goodale, who had come to Dresden for the sole purpose of finding them, with a request to make a series of glass botanical models for Harvard. Some reports claim that Goodale saw a few glass orchids in the room where they met, surviving from the work two decades earlier.[6] Leopold was unwilling: his current business of selling glass sea creatures was hugely successful but, eventually, he agreed to send test-models to the U.S. Though the items were badly damaged by U.S. Customs,[18] Goodale appreciated the fragmentary craftwork and showed them widely – convinced that Blaschka glass art was a more than worthy educational investment. His reasons for wanting the models was simple: At that time, Harvard was the global center of botanical study. As such, Goodale wanted the best, but the only used method was showcasing pressed and carefully labeled specimens — a methodology that offered a twofold problem: being pressed, the specimens were two-dimensional and tended to lose their color. Hence they were hardly the ideal teaching tools.[19][20] However, having already seen Harvard's recently procured glass marine invertebrates, Professor Goodale - like Professor Reichenbach before him - realized that glass flowers would solve his problem:[20] they were three-dimensional and would retain their color.

![A photo of the bouquet of glass flowers which, in 1889, Leopold Blaschka made and gifted to Elizabeth C. and Mary L. Ware which, at some later date, was given to Harvard and is now part of the Glass Flowers exhibit.[21]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/89/Glass_Flowers_gift-bouquet.jpg/220px-Glass_Flowers_gift-bouquet.jpg)

To cover the expensive enterprise, Goodale approached his former student Mary Lee Ware and her mother Elizabeth C. Ware; they were independently wealthy and already liberal benefactors of Harvard's botanical department.[22] Mary convinced her mother to agree to underwrite the consignment of the glass models that enchanted them both.[6] In 1887, the Blaschkas contracted to spend half-time producing the models for Harvard.[23] They continued to spend their remaining time making marine invertebrate models. However, in 1890, the Blaschkas insisted that it was impossible to craft the botanical models for half the year and the sea creatures the other half; "they said that they must give up either one or the other."[24] As such, that same year the Blaschkas signed an exclusive ten-year contract with Harvard to make glass flowers for 8,800 marks per year.[23] New arrangements were also made to send the models directly to Harvard, where museum staff could open them safely, observed by Customs staff.[6] They modeled a great range of plants (in total, 164 taxonomic families) and plant parts (flowers, leaves, fruits, roots). Some were shown during pollination by insects, others diseased in various ways.[1] Prof. Goodale noted that the activity of the Blaschkas was "greatly increased by their exclusive devotion to a single line of work."[24] In regards to Leopold's feelings for the Glass Flowers enterprise, and the change to it from the successful marine creature business, Goodale wrote the following in the Annual reports of the President and Treasurer of Harvard College 1890-1891:

It has been only within a comparatively short time that I have discovered the cause of the great reluctance of the elder Blaschka to the undertaking at the outset. It appears upon inquiry that he had constructed a few models of plants before beginning the preparation of the animal models to which he owes his wide celebrity; but these models of plants were, he thought, not appreciated by the persons for whom he had made them. The first set of models passed through various vicissitudes, and finally found a home in the Natural History Museum in Liège, where they were at last destroyed by fire. The artist did not have courage to undertake the experiment again, when he was succeeding so well with his animal models. He regards it as a pleasant turn in his fortunes which permits him to devote all of his time to the subject of his earliest studies.[24]

Production of Glass Flowers

Early in the making of Glass Flowers, Mary Lee Ware engaged in correspondence with Professor Goodale regarding the making of the collection, one of which contained a remark of Leopold's regarding the false rumor that secret methods were used in the making of the Glass Flowers: "Many people think that we have some secret apparatus by which we can squeeze glass suddenly into these forms, but it is not so. We have tact. My son Rudolf has more than I have, because he is my son, and tact increases in every generation."[6][7] On this trend, he also once said that "One cannot hurry glass. It will take its own time. If we try to hasten it beyond its limits, it resists and no longer obeys us. We have to humor it."[25]

The Blaschkas used a mixture of clear and coloured glass, sometimes supported with wire, to produce their models.[23] Many pieces were painted, this work being entirely given to Rudolf.[6] In order to represent plants which were not native to the Dresden area, the two studied the exotic plant collections at Pillnitz Palace[23] and the Dresden Botanical Garden, and also grew some from seed sent from the United States.[23] In 1892, Rudolf was sent on a trip to the Caribbean and the U.S. to study additional plants, making extensive drawings and notes.[6] At this point the number of glass models sent annually to Harvard was approximately 120.[24]

Rudolf made a second trip to the U.S. in 1895. While he was overseas - and eleven years into the project - Leopold died.[6] Rudolf continued to work alone, slowing down production so as to achieve higher levels of botanical perfection.[26] By the early twentieth century, he found that he was unable to buy glass of suitably high quality, and so started making his own.[23] This was confirmed by Mary Lee Ware during her 1908 visit to Rudolf in a letter she later wrote to the second director of the Botanical Museum, Professor Oakes Ames.[6] This letter appears to confirm the previous statement of Leopold's regarding his son; Miss Ware writes, "One change in the character of his work and, consequently in the time necessary to accomplish results since I was last here, is very noteworthy. At that time...he bought most of his glass and was just beginning to make some, and his finish was in paint. Now he himself makes a large part of the glass and all the enamels, which he powders to use as paint."[27] This missive to Professor Ames was published on January 9, 1961 by the Harvard University Herbaria - Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University Vol. 19, No. 6 - under the title "How Were The Glass Flowers Made?"[28] In addition to funding and visiting, Mary took an active role in the project's progress, going so far as to personally unpack each model[29][30] and making arrangements for Rudolph's fieldwork in the U.S. and Jamaica[29][30] – the purpose of such trips being to gather and study various plant specimens.

In 1911, Rudolf Blaschka married Frieda (whose maiden name is unknown) in a quiet wedding: "We had only a few guests but a great deal of people here had shown cordial interest...We took a four day wedding trip to visit the Ore mountains and the Zenkerhuette in Josefsthal a 200 year old glass factory where my great-grandfather was master about 130-150 years ago...we reached the remote place easily by the new railroad and we had right the last chance to see the interesting factory building. They are just going to pull it down and it will disappear". The couple hosted Mary L. Ware during the third of her three visits to Dresden, and they became very great friends.[11] In September 1923, Rudolf sent a letter to Mary stating that he had shipped four cases of specimens to the Museum in what was the first Glass Flowers shipment following World War I, but said that the complicated tax and inflation situation in Germany had left him without money and the Museum has not sent the 1923 payment yet. That November, he received $500 and a letter from Prof. Oakes Ames saying that Prof. Goodale had died that Ames was succeeding him, the money having been sent via Goodale's son Francis.[31] Ames was not as passionate about the Glass Flowers as his predecessor had been, seeing several unknown issues, but Ames soon requested what he referred to as "Economic Botany", asking Rudolf to make glass Olea europaea and Vitis vinifera, a request which Rudolf answered with alacrity and eventually evolved into a series of glass fruits in both rotting and edible condition.[31] However, Prof. Ames continued to exchange letters with Miss Ware discussing the project, namely the quality and speed of production as Rudolf ages, discussions which on Ames' part vary from controlled excitement to continued concern regarding the project and Rudolf's continuing ability to produce in a satisfactory manner.[31]

Rudolf continued making models for Harvard until 1938. By then aged 80, he announced that he would retire.[32] Neither he nor his father had taken on an apprentice, and Rudolf left no successor - he and Frieda Blaschka being childless.[1] For Harvard, Leopold and Rudolf made approximately 4,400 models, 780 showing species at life-size, with others showing magnified details; under 75% are, as of May 21, 2016, on display at the HMNH, (the exhibit itself dedicated to Dr. Charles Eliot Ware, the father of Mary Ware and husband of Elizabeth Ware); the old exhibit contained 3000 models but this number was reduced for renovation purposes.[23] Unlike the Glass sea creatures – "a profitable global mail-order business"[19] – the Glass Flowers were commissioned solely for and are unique to Harvard.

Legacy

Over the course of their collected lives Leopold and Rudolf crafted as many as ten thousand glass marine invertebrate models and 4,400 botanical ones that are the more famous Glass Flowers.[33][34]

The Blaschka studio survived the Bombing of Dresden in World War II so, in 1993, the Corning Museum and Harvard jointly purchased the remaining Blaschka studio materials from Frieda Blaschka's niece, Gertrud Pones.[35]

The Pisa Charterhouse houses the Museum of Natural History of the University of Pisa which includes a collection of 51 Blaschka glass marine invertebrates.[36]

Leopold and Rudolf and their spouses are buried together in the Hosterwitz cemetery in Dresden.

See also

- Robert Brendel

- The Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants, Harvard Museum of Natural History

- Blaschka Collection, Museum of Natural History of the University of Pisa

References

- Dühning, Johanna. "The Association "Naturwissenschaftliche Glaskunst - Blaschka-Haus e.V."". urania-dresden.de. Translated by Pentzold, Benjamin. Archived from the original on September 10, 2002.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - "Leopold + Rudolf Blaschka: The Glass Aquarium". designmuseum.org. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- Sigwart, Julia D. "Crystal creatures: context for the Dublin Blaschka Congress." Historical Biology 20.1 (2008): 1-10.

- Harvell, Drew (May 2016). A Sea of Glass: Searching for the Blaschkas’ Fragile Legacy in an Ocean at Risk. Organisms and Environments, 13. (1st, hardcover ed.). Oakland: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-28568-2. LCCN 2015029740. Wikidata Q114635674.

- The German word used here is takt, usually translated as "tact" in English. The German word has several different meanings, and in some cases is translated as "subtlety" or "heartbeat". In this context "the touch" or "the feeling" is closer to the intended meaning than the usual "tact". https://m.interglot.com/de/en/Takt

- Schultes, Richard Evans; Davis, William A.; Burger, Hillel (1982). The Glass Flowers at Harvard. New York: Dutton. Excerpt available at: "The Fragile Beauty of Harvard's Glass Flowers". The Journal of Antiques and Collectibles. February 2004. Archived from the original on 2016-04-11. Retrieved 2015-06-10.

- Richard, Frances (Spring 2002). "Great Vitreous Tract". Cabinet Magazine.

- "Heraldika a genealogie č. 1 - 2/2010" (PDF). 2011.

- The Story of Rudolf and Leopold Blaschka - https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHOx5H5vNx4

- Whitehouse, David (November 3, 2011). "Blaschkas' Glass Models of Invertebrate Animals (1863–1890)". Corning Museum of Glass.

- Harvard University Herbaria and Libraries

- Leibach, Julie (May 13, 2016). "A Tale of Two Glassworkers and Their Marine Marvels". Science Friday.

- "The Blaschka Archive". Corning Museum of Glass.

- Blaschka, L. (1885). Katalog über Blaschka's Modelle. Dresden. Available from: Museum of Natural History Berlin, Historical Collection of Pictures and Writings

- "Sea creatures of the deep - the Blaschka Glass models". National Museum Wales. May 15, 2007.

- "The Delicate Glass Sea Creatures of Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka". Atlas Obscura. September 1, 2016.

- TréZOOr Museum [dead link]

- "The Glass Flowers". Corning Museum of Glass. October 18, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- "The Glass Flowers". Harvard Museum of Natural History. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- B. L. Robinson (Autumn 1924). "Biographical Memoir George Lincoln Goodale 1839–1923" (PDF). Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences: Volume XXI. National Academy of Sciences. Retrieved June 10, 2015.

- Rossi-Wilcox, Susan M. "A Brief History of Harvard's Glass Flowers Collection and Its Development." Journal of Glass Studies (2015): 197-211.

- Wiley, Franklin Baldwin (1897). Flowers That Never Fade. Boston: Bradlee Whidden.

- Emison, Patricia A. (2005). Growing With the Grain: Dynamic Families Shaping History from Ancient Times to the Present. Lady Illyria Press. p. 184. ISBN 9780976557203.

- Annual reports of the President and Treasurer of Harvard College 1890-1891, pp. 160-163 - https://iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:427018526$1i

- McFadden, Robert D. (1976-03-08). "Blaschka Plants Blend Science and Artistry". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2022-07-03.

- "The Blaschka Flower Models". Popular Science. March 1897. p. 668.

- Daston, Lorraine (2004). Things That Talk: Object Lessons from Art and Science. New York: Zone.

- Ware, Mary Lee (1961). "How were the glass flowers made?". Botanical Museum Leaflets, Harvard University. 19 (6): 125–136. doi:10.5962/p.168528. JSTOR 41762212. S2CID 192127292.

- "The Archives of Rudolph and Leopold Blaschka and the Ware Collection of Blaschka Glass Models of Plants". Harvard University Herbaria. Retrieved 14 January 2016.

- Rossi-Wilcox, Susan M. (January 15, 2013). "Blaschkas' Glass Botanical Models (1886–1936)". Corning Museum of Glass.

- Oakes Ames Correspondence: Botany Libraries, Archives of the Economic Botany Herbarium of Oakes Ames, Harvard University Herbaria

- "Bohemian maker's retirement completes Harvard glass-flower collection". Life. February 28, 1938. p. 24.

- "Back to Back Bay After an Absence of Ten Years". The New York Times. June 10, 1951. p. XX17.

- Swinney, Geoffrey N. (2008-02-01). "Enchanted invertebrates: Blaschka models and other simulacra in National Museums Scotland". Historical Biology. 20 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1080/08912960701677036. ISSN 0891-2963. S2CID 84854344.

- Drawing upon Nature: Studies for the Blaschkas’ Glass Models - http://www.cmog.org/publication/drawing-upon-nature-studies-blaschkas-glass-models-0

- "Leopold and Rudolf Blaschka Collection, Natural History Museum of the University of Pisa".

External links

- The Story of Rudolf and Leopold Blaschka, video

- The Blaschka Archives, held by the Rakow Library of the Corning Museum of Glass.

- Blaschka collection at Natural History Museum, London

- "Sea creatures of the deep - the Blaschka Glass models" National Museum of Wales. 15 May 2007.

- "The Glass Flowers". Corning Museum of Glass. Corning Museum of Glass. 18 October 2011. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- Out of the Teeming Sea: Cornell Collection of Blaschka Invertebrate Models

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии