art.wikisort.org - Painting

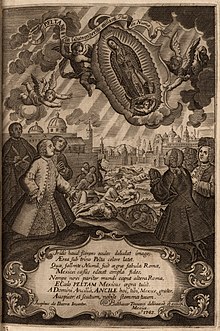

Our Lady of Guadalupe (Spanish: Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe), also known as the Virgin of Guadalupe (Spanish: Virgen de Guadalupe), is a Catholic title of Mary, mother of Jesus associated with a series of five Marian apparitions, which are believed to have occurred in December 1531, and a venerated image on a cloak enshrined within the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City. The basilica is the most-visited Catholic shrine in the world, and the world's third most-visited sacred site.[1][2]

| Our Lady of Guadalupe | |

|---|---|

| |

| Location | Tepeyac Hill, Mexico City |

| Date | 12 December 1531 (on the Julian calendar, which would be December 22 on the Gregorian calendar now in use). |

| Witness | Juan Diego Juan Bernardino |

| Type | Marian apparition |

| Approval | 12 October 1895 (canonical coronation granted by Pope Leo XIII) |

| Shrine | Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Tepeyac Hill, Mexico City, Mexico |

| Patronage | Mexico (2018) The Americas (October 12, 1945) Cebu (2002 by Ricardo Vidal) |

| Attributes | A pregnant woman, eyes downcast, hands clasped in prayer, clothed in a pink tunic robe covered by a cerulean mantle with a black sash, emblazoned with eight-point stars; eclipsing a blazing sun while standing atop a darkened crescent moon, a cherubic angel carrying her train |

Pope Leo XIII granted the image a decree of canonical coronation on 8 February 1887 and was pontifically crowned on 12 October 1895.

Description of Marian apparitions

According to Nican Mopohua, a 17th-century account written in the native Nahuatl language, the Virgin Mary appeared four times to Juan Diego, an indigenous Mexican peasant Chichimec and once to his uncle, Juan Bernardino. The first apparition occurred on the morning of Saturday, 9 December 1531 (Julian calendar, which is December 19 on the (proleptic) Gregorian calendar in present use). Juan Diego experienced a vision of a young woman at a place called the Hill of Tepeyac, which later became part of Villa de Guadalupe, in a suburb of Mexico City.[3] According to the accounts, the woman, speaking to Juan Diego in his native Nahuatl language (the language of the Aztec Empire), identified herself as the Virgin Mary, "mother of the very true deity".[4] She was said to have asked for a church to be erected at that site in her honor.[3] Based on her words, Juan Diego then sought the Archbishop of Mexico City, Fray Juan de Zumárraga, to tell him what had happened. Not unexpectedly, the Archbishop did not believe Diego. Later the same day, Juan Diego again saw the young woman (the second apparition), and she asked him to continue insisting.[3]

The next day, Sunday, December 10, 1531 (Julian calendar), Juan Diego spoke to the Archbishop a second time. The latter instructed him to return to Tepeyac Hill and to ask the woman for a truly acceptable, miraculous sign to prove her identity. Later that day, the third apparition appeared when Juan Diego returned to Tepeyac; encountering the same woman, he reported to her the Archbishop's request for a sign, which she consented to provide on the next day (December 11).[5]

By Monday, December 11 (Julian calendar), however, Juan Diego's uncle, Juan Bernardino, became ill, which obligated Juan Diego to attend to him. In the very early hours of Tuesday, December 12 (Julian calendar), Juan Bernardino's condition having deteriorated overnight, Juan Diego journeyed to Tlatelolco to get a Catholic priest to hear Juan Bernardino's confession and help minister to him on his deathbed.[3]

To avoid being delayed by the Virgin and ashamed at having failed to meet her on Monday as agreed, Juan Diego chose another route around Tepeyac Hill, yet the Virgin intercepted him and asked where he was going (fourth apparition); Juan Diego explained what had happened and the Virgin gently chided him for not having made recourse to her. In the words which have become the most famous phrase of the Guadalupe apparitions and are inscribed above the main entrance to the Basilica of Guadalupe, she asked "¿No estoy yo aquí que soy tu madre?" ("Am I not here, I who am your mother?"). She assured him that Juan Bernardino had now recovered and told him to gather flowers from the summit of Tepeyac Hill, which was normally barren, especially in the cold of December. Juan Diego obeyed her instruction and he found Castilian roses, not native to Mexico, blooming there.[3]

According to the story, the Virgin arranged the flowers in Juan Diego's tilma, or cloak, and when Juan Diego opened his cloak later that day before Archbishop Zumárraga, the flowers fell to the floor, revealing on the fabric the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe.[3]

The next day, December 13 (Julian calendar), Juan Diego found his uncle fully recovered as the Virgin had assured him, and Juan Bernardino recounted that he also had seen her after praying at his bedside (fifth apparition); that she had instructed him to inform the Archbishop of this apparition and of his miraculous cure; and that she had told him she desired to be known under the title of 'Guadalupe'.[3]

The Archbishop kept Juan Diego's mantle, first in his private chapel and then in the church on public display, where it attracted great attention. On December 26, 1531, a procession formed to transfer the miraculous image back to Tepeyac Hill where it was installed in a small, hastily erected chapel.[6] During this procession, the first miracle was allegedly performed when a native was mortally wounded in the neck by an arrow shot by accident during some stylized martial displays performed in honor of the Virgin. In great distress, the natives carried him before the Virgin's image and pleaded for his life. Upon the arrow being withdrawn, the victim fully and immediately recovered.[7]

Pontifical approbations

- Pope Benedict XIV — in the papal bull Non est Equidem of 25 May 1754, declared Our Lady of Guadalupe patroness of what was then named "New Spain", corresponding to Spanish Central and Northern America, and included liturgical texts for the Catholic Mass and the Roman Breviary in her honor.

- Pope Leo XIII — granted a decree of coronation towards the original Mexican relic on 8 February 1887. Later, through the Sacred Congregation of Rites, he issued an addendum epistle of endorsement on 6 March 1894. The rite of coronation which was executed on 12 October 1895.

- Pope Pius X — declared her patroness of the Republic of Mexico on 16 June 1910 via decree Gratia Quae, signed and notarized by Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val.[8]

- Pope Pius XI — granted a decree of canonical coronation for a namesake image enshrined in Santa Fe, Argentina on 10 August 1924, executed by Archbishop Filippo Cortesi on 22 April 1928. Pius XI declared Our Lady of Guadalupe as the "Heavenly Patroness of the Philippines" on 16 July 1935, signed by Vatican Secretary of State Cardinal Eugenio Pacelli.[9][10] He later issued a decree confirming the patronage of Guadalupe for the Diocese of Coro, Venezuela at the “Second Marian National Congress” on 12 December 1928.

- Pope Pius XII — rescinded the former decrees of July 1935 in replacement of Impositi Nobis on 12 September 1942[11] and further redeclared it again via Quidquid ad Dilatandum on 16 July 1958[12] in preference of the Patronal title "Immaculate Conception" for the Philippine islands. He also mentioned the venerated image via public radio address honoring its fiftieth anniversary of coronation on 12 October 1945.[13]

- Pope Paul VI — granted the image a Golden Rose on 20 March 1966. In accordance with tradition, he blessed the rose, the work of the Roman sculptor Giuseppe Pirrone, on Laetare Sunday, 20 March 1966 and consigned it to Cardinal Confalonieri as his legate, who presented it at the Basilica on 31 May 1966.[14]

- Pope John Paul II — visited her shrine on 26 January 1979, and again when he beatified Juan Diego there on 6 May 1990. Later, he issued a decree of Canonical coronation for the same namesake image for the cloister of the Claretian Order of sisters on 10 December 1980 in Suginami, Tokyo, Japan. On 12 May 1992, he dedicated a namesake chapel within the grottoes under Saint Peter's Basilica at the Vatican. John Paul II granted another decree of coronation for a statue image bearing the same name in Coro, Venezuela on 8 October 1992 and another for Manzanillo, Mexico on 15 September 1994, both signed and executed by Cardinal Angelo Sodano at the Vatican. He then included in the General Roman Calendar as an optional memorial the liturgical celebration of this Marian title in 2002.

- Pope Benedict XVI — granted a decree of canonical coronation for the same namesake image for Cebu, Philippines on 16 July 2006, marking his second decree of coronation. He later issued a decree raising the shrine of Guadalupe in Coro, Venezuela to the status of Minor Basilica on 6 December 2008.

- Pope Francis — granted the image a second Golden Rose via Cardinal Marc Ouellet for presentation at the Basilica on 18 November 2013.[15] He later granted a new gold-plated silver crown with an accompanying prayer to the image during his apostolic visit to the Basilica on 13 February 2016. On the crown was inscribed "Mater Mea, Spes Mea" ("My Mother [and] My Hope"). This crown is stored within the chancery and is not publicly worn by the image enshrined at the altar. Francis granted a decree of Canonical coronation for the same namesake image in Villa Garcia, Zacatecas,[16] Mexico dated on 14 June 2015.

Early history

Origin in Guadalupe, Spain

The shrine to Our Lady of Guadalupe in Guadalupe, Cáceres, in Extremadura, Spain was[when?] the most important Marian shrine in the medieval kingdom of Castile.[17] It is one of the many dark or black skinned Madonnas in Spain and is revered in the Monastery of Santa María de Guadalupe, in the town of Guadalupe, from which numerous Spanish conquistadors stem. The name is believed to be derived from the Arabic phrase وادي اللب, "Wad-al-lubb" ("hidden river"), because the river narrows down as it flows near to the town of Guadalupe.[citation needed]

The shrine houses a statue reputed to have been carved by Luke the Evangelist and given to Leander of Seville, archbishop of Seville, by Pope Gregory I. According to local legend, when Seville was taken by the Moors in 712, a group of priests fled northward and buried the statue in the hills near the Guadalupe River. At the beginning of the 14th century, the Virgin appeared one day to a humble cowboy named Gil Cordero who was searching for a missing animal in the mountains.[18] Cordero claimed that the Virgin Mary had appeared to him and ordered him to ask priests to dig at the site of the apparition. Excavating priests rediscovered the hidden statue and built a small shrine around it which became the great Guadalupe monastery.[citation needed]

Origin in Mexico

Following the Conquest in 1519–1521, the Marian cult was brought to the Americas and Franciscan friars often leveraged syncretism with existing religious beliefs as an instrument for evangelization. What is purported by some to be the earliest mention of the miraculous apparition of the Virgin is a page of parchment, the Codex Escalada from 1548, which was discovered in 1995 and, according to investigative analysis, dates from the sixteenth century.[19] This document bears two pictorial representations of Juan Diego and the apparition, several inscriptions in Nahuatl referring to Juan Diego by his Aztec name, and the date of his death: 1548, as well as the year that the then named Virgin Mary appeared: 1531. It also contains the glyph of Antonio Valeriano; and finally, the signature of Fray Bernardino de Sahagun which was authenticated by experts from the Banco de Mexico and Charles E. Dibble.[20] Scholarly doubts have been cast on the authenticity of the document.[21]

A more complete early description of the apparition occurs in a 16-page manuscript called the Nican mopohua, which has been reliably dated in 1556 and was acquired by the New York Public Library in 1880. This document, written in Nahuatl, but in Latin script, tells the story of the apparitions and the supernatural origin of the image. It was probably composed by a native Aztec man, Antonio Valeriano, who had been educated by Franciscans. The text of this document was later incorporated into a printed pamphlet which was widely circulated in 1649.[22][23][24][25]

In spite of these documents, there are no 16th century written accounts of the Guadalupe vision by the archbishop Juan de Zumárraga, as there ought to have been, if the event had the Christian importance it is said to have had.[26] In particular, the canonical account of the vision features archbishop Juan de Zumárraga as a major player in the story, but, although Zumárraga was a prolific writer, there is nothing in his extant writings that can confirm the indigenous story.[27]

The written record suggests the Catholic clergy in 16th century Mexico were deeply divided as to the orthodoxy of the native beliefs springing up around the image of Our Lady of Guadalupe, with the Franciscan order (who then had custody of the chapel at Tepeyac) being strongly opposed to the outside groups, while the Dominicans supported it.[28]

The main promoter of the story was the Dominican Alonso de Montúfar, who succeeded the Franciscan Juan de Zumárraga as archbishop of Mexico. In a 1556 sermon Montúfar commended popular devotion to "Our Lady of Guadalupe", referring to a painting on cloth (the tilma) in the chapel of the Virgin Mary at Tepeyac, where certain miracles had also occurred. Days later, Fray Francisco de Bustamante, local head of the Franciscan order, delivered a sermon denouncing the native belief and believers. He expressed concern that the Catholic Archbishop was promoting a superstitious regard for an indigenous image:[29]

The devotion at the chapel... to which they have given the name Guadalupe was prejudicial to the Indians because they believed that the image itself worked miracles, contrary to what the missionary friars had been teaching them, and because many were disappointed when it did not.

Archbishop Montúfar opened an inquiry into the matter at which the Franciscans repeated their position that the image encouraged idolatry and superstition, and four witnesses testified to Bustamante's statement that the image was painted by an Indian, with one witness naming him "the Indian painter Marcos".[30] This could refer to the Aztec painter Marcos Cipac de Aquino, who was active at that time.[31][32]

Prof. Jody Brant Smith, referring to Philip Serna Callahan's examination of the tilma using infrared photography in 1979, wrote: "if Marcos did, he apparently did so without making a preliminary sketches – in itself then seen as a near-miraculous procedure... Cipac may well have had a hand in painting the Image, but only in painting the additions, such as the angel and moon at the Virgin's feet",[33]

Ultimately Archbishop Montúfar, himself a Dominican, decided to end Franciscan custody of the shrine.[34] From then on the shrine was kept and served by diocesan priests under the authority of the archbishop.[35] Moreover, Archbishop Montúfar authorized the construction of a much larger church at Tepeyac, in which the tilma was later mounted and displayed.[citation needed]

In the late 1570s, the Franciscan historian Bernardino de Sahagún denounced the cult at Tepeyac and the use of the name "Tonantzin" or to call her Our Lady in a personal digression in his General History of the Things of New Spain, also known as the "Florentine Codex":

At this place [Tepeyac], [the Indians] had a temple dedicated to the mother of the gods, whom they called Tonantzin, which means Our Mother. There they performed many sacrifices in honor of this goddess ... And now that a church of Our Lady of Guadalupe is built there, they also called her Tonantzin, being motivated by those preachers who called Our Lady, the Mother of God, Tonantzin. While it is not known for certain where the beginning of Tonantzin may have originated, but this we know for certain, that, from its first usage, the word refers to the ancient Tonantzin. And it was viewed as something that should be remedied, for their having [native] name of the Mother of God, Holy Mary, instead of Tonantzin, but Dios inantzin. It appears to be a Satanic invention to cloak idolatry under the confusion of this name, Tonantzin. And they now come to visit from very far away, as far away as before, which is also suspicious, because everywhere there are many churches of Our Lady and they do not go to them. They come from distant lands to this Tonantzin as in olden times.[36]

Sahagún's criticism of the indigenous group seems to have stemmed primarily from his concern about a syncretistic application of the native name Tonantzin to the Catholic Virgin Mary. However, Sahagún often used the same name in his sermons as late as the 1560s.[37]

First printed accounts in Mexico

One of the first printed accounts of the history of the apparitions and image occurs in Imagen de la Virgen Maria, Madre de Dios de Guadalupe, published in 1648 by Miguel Sánchez, a diocesan priest of Mexico City.[38]

Another account is the Codex Escalada, dating from the sixteenth century, a sheet of parchment recording apparitions of the Virgin Mary and the figure of Juan Diego, which reproduces the glyph of Antonio Valeriano alongside the signature of Fray Bernardino de Sahagún. It contains the following glosses: "1548 Also in that year of 1531 appeared to Cuahtlatoatzin our beloved mother the Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico. Cuahtlatoatzin died worthily"[39]

The next printed account was a 36-page tract in the Nahuatl language, Huei tlamahuiçoltica ("The Great Event"), which was published in 1649. This tract contains a section called the Nican mopohua ("Here it is recounted"), which has been already touched on above. The composition and authorship of the Huei tlamahuiçoltica is assigned by a majority of those scholars to Luis Laso de la Vega, vicar of the sanctuary of Tepeyac from 1647 to 1657.[40] Nevertheless, the most important section of the tract, the Nican Mopohua, appears to be much older. It has been attributed since the late 1600s to Antonio Valeriano (c. 1531–1605), a native Aztec man who had been educated by the Franciscans and who collaborated extensively with Bernardino de Sahagún.[22] A manuscript version of the Nican Mopohua, which is now held by the New York Public Library,[41] appears to be datable to the mid-1500s, and may have been the original work by Valeriano, as that was used by Laso in composing the Huei tlamahuiçoltica. Most authorities agree on the dating and on Valeriano's authorship.[23][24][25]

On the other hand, in 1666, the scholar Luis Becerra Tanco published in Mexico a book about the history of the apparitions under the name "Origen milagroso del santuario de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe," which was republished in Spain in 1675 as "Felicidad de Mexico en la admirable aparición de la virgen María de Guadalupe y origen de su milagrosa Imagen, que se venera extramuros de aquella ciudad."[42] In the same way, in 1688, Jesuit Father Francisco de Florencia published La Estrella del Norte de México, giving the history of the same apparitions.[43]

Two separate accounts, one in Nahuatl from Juan Bautista del Barrio de San Juan from the 16th century,[44] and the other in Spanish by Servando Teresa de Mier[45] date the original apparition and native celebration on September 8 of the Julian calendar, but it is also said that the Spaniards celebrate it on December 12 instead.[citation needed]

According to the document Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666, a Catholic feast day in name of Our Lady of Guadalupe was requested and approved, as well as the transfer of the date of the feast of the Virgin of Guadalupe from September 8 to December 12, the latest date on which the Virgin supposedly appeared to Juan Diego. The initiative to perform them was made by Francisco de Siles who proposed to ask the Church of Rome, a Mass itself with allusive text to the apparitions and stamping of the image, along with the divine office itself, and the precept of hearing a Catholic Mass on December 12, the last date of the apparitions of the Virgin to Juan Diego as the new date to commemorate the apparitions (which until then was on September 8, the birth of the Virgin).[46]

In 1666, the Church in México began gathering information from people who reported having known Juan Diego, and in 1723 a formal investigation into his life was ordered, where more data was gathered to support his veneration. Because of the Informaciones Jurídicas de 1666 in the year 1754, the Sacred Congregation of Rites confirmed the true and valid value of the apparitions, and granted celebrating Mass and Office for the then Catholic version of the feast of Guadalupe on December 12.[47][48]

These published accounts of the origin of the image already venerated in Tepeyac, then increased interest in the identity of Juan Diego, who was the original recipient of the prime vision. A new Catholic Basilica church was built to house the image. Completed in 1709, it is now known as the Old Basilica.[49]

The crown ornament

![Virgen de Guadalupe con las cuatro apariciones by Juan de Sáenz (Virgin of Guadalupe with the four apparitions by Juan de Sáenz), c. 1777, at the Museo Soumaya[50]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/72/Virgen_de_Guadalupe_con_las_cuatro_apariciones_%28Juan_de_S%C3%A1enz%29_Detalle_%2801%29.JPG/250px-Virgen_de_Guadalupe_con_las_cuatro_apariciones_%28Juan_de_S%C3%A1enz%29_Detalle_%2801%29.JPG)

The image[which?] had originally featured a 12-point crown on the Virgin's head, but this disappeared in 1887–88. The change was first noticed on February 23, 1888, when the image was removed to a nearby church.[51] Eventually a painter confessed on his deathbed that he had been instructed by a clergyman to remove the crown. This may have been motivated by the fact that the gold paint was flaking off of the crown, leaving it looking dilapidated. But according to the historian David Brading, "the decision to remove rather than replace the crown was no doubt inspired by a desire to 'modernize' the image and reinforce its similarity to the nineteenth-century images of the Immaculate Conception which were exhibited at Lourdes and elsewhere... What is rarely mentioned is that the frame which surrounded the canvas was adjusted to leave almost no space above the Virgin's head, thereby obscuring the effects of the erasure."[52]

A different crown was installed to the image. On February 8, 1887, a Papal bull from Pope Leo XIII granted permission a Canonical Coronation of the image, which occurred on October 12, 1895.[53] Since then the Virgin of Guadalupe has been proclaimed "Queen of Mexico", "Patroness of the Americas", "Empress of Latin America", and "Protectress of Unborn Children" (the latter two titles given by Pope John Paul II in 1999).[9][54]

The beatification of Juan Diego

Under Pope John Paul II the move to beatify Juan Diego intensified. John Paul II took a special interest in non-European Catholics and saints. During his leadership, the Congregation for the Causes of Saints declared Juan Diego "venerable" (in 1987), and the pope himself announced his beatification on May 6, 1990, during a Mass at the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe in Mexico City, declaring him "protector and advocate of the indigenous peoples," with December 9 established as his feast day.[55]

At that time historians revived doubts as to the quality of the evidence regarding Juan Diego. The writings of bishop Zumárraga, into whose hands Juan purportedly delivered the miraculous image, did not refer to him or the event. The record of the 1556 ecclesiastical inquiry omitted him, and he was not mentioned in documentation before the mid-17th century. In 1996 the 83-year-old abbot of the Basilica of Guadalupe, Guillermo Schulenburg, was forced to resign following an interview published in the Catholic magazine Ixthus, in which he was quoted as saying that Juan Diego was "a symbol, not a reality", and that his canonization would be the "recognition of a cult. It is not recognition of the physical, real existence of a person."[56] In 1883 Joaquín García Icazbalceta, historian and biographer of Zumárraga, in a confidential report on the Lady of Guadalupe for Bishop Labastida, had been hesitant to support the story of the vision. He concluded that Juan Diego had not existed.[57]

In 1995, Father Xavier Escalada, a Jesuit whose four volume Guadalupe encyclopedia had just been published, announced the existence of a sheet of parchment (known as Codex Escalada), which bore an illustrated account of the vision and some notations in Nahuatl concerning the life and death of Juan Diego. Previously unknown, the document was dated 1548. It bore the signatures of Antonio Valeriano and Bernardino de Sahagún, which are considered to verify its contents. The codex was the subject of an appendix to the Guadalupe encyclopedia, published in 1997.[21] Some scholars remained unconvinced, one describing the discovery of the Codex as "rather like finding a picture of St. Paul's vision of Christ on the road to Damascus, drawn by St. Luke and signed by St. Peter."[58]

Marian title

In the earliest account of the apparition, the Nican Mopohua, the Virgin de Guadalupe, later called as if the Virgin Mary tells Juan Bernardino, the uncle of Juan Diego, that the image left on the tilma is to be known by the name "the Perfect Virgin, Holy Mary of Guadalupe."[59]

The Virgin of Guadalupe is a core element of Mexican identity and with the rise of Mexican nationalism and indigenist ideologies, there have been numerous efforts to find a pre-Hispanic origin in the cult, to the extreme of attempting to find a Nahuatl etymology to the name.[citation needed]

The first theory to promote a Nahuatl origin was that of Luis Becerra Tanco.[60] In his 1675 work Felicidad de Mexico, Becerra Tanco said that Juan Bernardino and Juan Diego would not have been able to understand the name Guadalupe because the "d" and "g" sounds do not exist in Nahuatl.[citation needed]

He proposed two Nahuatl alternative names that sound similar to "Guadalupe", Tecuatlanopeuh [tekʷat͡ɬaˈnopeʍ], which he translates as "she whose origins were in the rocky summit", and Tecuantlaxopeuh [tekʷant͡ɬaˈʃopeʍ], "she who banishes those who devoured us."[60]

Ondina and Justo González suggest that the name is a Spanish version of the Nahuatl term, Coātlaxopeuh [koaːt͡ɬaˈʃopeʍ], which they interpret as meaning "the one who crushes the serpent," and that it may seem to be referring to the feathered serpent Quetzalcoatl. In addition, the Virgin Mary was portrayed in European art as crushing the serpent of the Garden of Eden.[61]

According to another theory the juxtaposition of Guadalupe and a snake may indicate a nexus with the Aztec goddess of love and fertility, Tonantzin (in Nahuatl, "Our Revered Mother"), who was also known by the name Coatlícue ("The Serpent Skirt"). This appears to be borne out by the fact that this goddess already had a temple dedicated to her on the very Tepeyac Hill where Juan Diego had his vision, the same temple which had recently been destroyed at the behest of the new Spanish Catholic authorities. In the 16th century the Franciscans were suspicious that the followers of Guadalupe showed, or was susceptible to, elements of syncretism, i.e. the importation of an object of reverence in one belief system into another (see above).[citation needed]

The theory promoting the Spanish origin of the name says that:

- Juan Diego and Juan Bernardino would have been familiar with the Spanish "g" and "d" sounds since their baptismal names contain those sounds.

- There is no documentation of any other name for this Marian apparition during the almost 144 years between the apparition being recorded in 1531 and Becerra Tanco's proposed theory in 1675.

- Documents written by contemporary Spaniards and Franciscan friars argue that for the name to be changed to a native name, such as Tepeaca or Tepeaquilla, would not make sense to them, if a Nahuatl name were already in use, and suggest the Spanish Guadalupe was the original.[60]

Venerated image and Diego's tilma

Iconographic description

The venerated image of Our Lady of Guadalupe features a full-length representation of a young woman with delicate features and straight, dark hair in a centre parting. She stands facing the viewer's left, with her hands joined in prayer and head slightly inclined down, gazing with heavy-lidded eyes at a spot below and to her right (the left of the viewer).

The figure is dressed from neck to feet in a pink robe and cerulean mantle, one side folded within the arms, emblazoned with eight-pointed stars with two black tassels tied high around her waist, and wearing a neck brooch featuring a colonial-style cross. The robe is spangled with a small gold quatrefoil motif ornamented with vines and flowers, its sleeves reaching to her wrists where the cuffs of a white undergarment appear.

The figure stands on an upturned crescent moon, which was allegedly once silver in colour, and is now relatively dark. A feathered cherubic angel with outstretched arms carries the corners of her robe underneath her exposed feet. A sunburst of straight and wavy gold rays are projected behind her and around her and are enclosed within a mandorla. Beyond the mandorla to the right and left is an unpainted expanse, white in color with a faint blue tinge.

The present image shows the 1791 nitric acid spill on the top right side, unaffecting the subject matter's aureola.[upper-alpha 1][62]

Physical description

The portrait was executed on a natural fibre fabric support constituted by two pieces (originally three) joined. The join is clearly visible as a seam passing from top to bottom, with the Virgin's face and hands and the head of the angel on the left piece, passing through the left wrist of the Virgin. The fabric is mounted on a large metal sheet to which it has been glued for some time.[63] The image, currently set in a massive frame protected behind bullet-proof glass, hangs inclined at a slight angle on the wall of the basilica behind the altar. At this point, there is a wide gap between the wall and the sanctuary facilitating closer viewing from moving walkways set on the floor beneath the main level of the basilica, carrying people a short distance in either direction. Viewed from the main body of the basilica, the image is located above and to the right of the altar and is retracted at night into a small vault (accessible by steps) set into the wall.[64] An intricate metal crown designed by the painter Salomé Pina according to plans devised by Rómulo Escudero and Pérez Gallardo, and executed by the Parisian goldsmith, Edgar Morgan, is fixed above the image by a rod, and a massive Mexican flag is draped around and below the frame.[65]

The nature of the fabric is discussed below. Its measurements were taken by José Ignacio Bartolache on December 29, 1786, in the presence of José Bernardo de Nava, a public notary: height 170 cm (67 in), width 105 cm (41 in).[66] The original height (before it was first shielded behind glass in the late 18th century, at which time the unpainted portion beyond the Virgin's head must have been cut down) was 229 cm (90 in).[67]

Technical analyses

Neither the fabric ("the support") nor the image (together, "the tilma") has been analyzed using the full range of resources now available to museum conservators. Four technical studies have been conducted so far. Of these, the findings of at least three have been published. Each study required the permission of the custodians of the tilma in the Basilica. However, Callahan's study was taken at the initiative of a third party: the custodians did not know in advance what his research would reveal.

- Miguel Cabrera, 1756 – in 1756 a prominent artist, Miguel Cabrera, published a report entitled Maravilla Americana, containing the results of the ocular and manual inspections by him and six other painters in 1751 and 1752.[68][69]

- José Gómez, 1947 and 1973 – José Antonio Flores Gómez, an art restorer, discussed in a 2002 interview with the Mexican journal Proceso, certain technical issues relative to the tilma. He had worked on it in 1947 and 1973.[70]

- Philip Callahan, 1979 – in 1979 Philip Callahan, a biophysicist, USDA entomologist, and NASA consultant specializing in infrared imaging, was allowed direct access to visually inspect, and photograph, the image. He took numerous infrared photographs of the front of the tilma. Taking notes that were later published, his assistant said that the original art work was neither cracked nor flaked, while later additions (gold leaf, silver plating the Moon) showed serious signs of wear, if not complete deterioration. Callahan could not explain the excellent state of preservation of the un-retouched areas of the image on the tilma, particularly the upper two-thirds of the image. His findings, with photographs, were published in 1981.[71][72]

- José Rosales, 1982 – in 2002 Proceso published an interview with José Sol Rosales, formerly director of the Center for the Conservation and Listing of Heritage Artifacts (Patrimonio Artístico Mueble) of the National Institute of Fine Arts (INBA) in México City. The article included extracts from a report which Rosales had written in 1982 of his findings from his inspection of the tilma that year using raking and UV light. It was done at low magnification with a stereo microscope of the type used for surgery.[73][74][75]

Summary conclusions were ("contra" indicates a contrary finding):

- Canvas support: The material of the support is soft to the touch (described as "almost silken" by Cabrera and "something like cotton" by Gómez) but to the eye suggests a coarse weave of palm threads called "pita" or the rough fiber called "cotense" (Cabrera), or a hemp and linen mixture (Rosales). It was traditionally held to be made from ixtle, an agave fiber.

- Ground, or primer: Rosales asserted (Cabrera and Callahan contra) by ocular examination that the tilma was primed, though with primer "applied irregularly." Rosales does not clarify whether his observed "irregular" application entails that majorly the entire tilma was primed, or just certain areas—such as those areas of the tilma extrinsic to the image—where Callahan agrees had later additions. Cabrera, alternatively, observed that the image had soaked through to the reverse of the tilma.[76]

- Under-drawing: Callahan asserted there was no under-drawing.

- Brush-work: Rosales suggested (Callahan contra) there was some visible brushwork on the original image, but in a minute area of the image ("her eyes, including the irises, have outlines, apparently applied by a brush").

- Condition of the surface layer: Callahan reports that the un-retouched portions of the image, particularly the blue mantle and the face, are in a very good state of preservation, with no flaking or peeling. The three most recent inspections (Gómez, Callahan and Rosales) agree (i) that additions have been made to the image (gold leaf added to the Sun's rays—which has flaked off; silver paint or other material to depict the Moon—which has discolored; and the re-construction or addition of the angel supporting the Marian image), and (ii) that portions of the original image have been abraded and re-touched in places. Some flaking is visible, though only in retouched areas (mostly along the line of the vertical seam, or at passages considered to be later additions).

- Varnish: The tilma has never been varnished.

- Binding medium: Rosales provisionally identified the pigments and binding medium (distemper) as consistent with 16th-century methods of painting sargas (Cabrera, Callahan contra for different reasons), but the color values and luminosity are in good condition. The technique of painting on fabric with water-soluble pigments (with or without primer or ground) is well-attested. The binding medium is generally animal glue or gum arabic (see distemper). Such an artifact is variously discussed in the literature as a tüchlein or sarga.[77][78] Tüchlein paintings are very fragile, and are not well preserved,[79] so the tilma's color values and state of preservation are very good.

Trans-religious significance

Religious imagery of Our Lady of Guadalupe appears in Roman Catholic parishes, especially those with Latin American heritage.[80] In addition, due to the growth of Hispanic communities in the United States, religious imagery of Our Lady of Guadalupe has started appearing in some Anglican, Lutheran, and Methodist churches.[80] Additionally, Our Lady of Guadalupe is venerated by some Mayan Orthodox Christians in Guatemala.[81]

The iconography of the Virgin is fully Catholic:[82] Miguel Sánchez, the author of the 1648 tract Imagen de la Virgen María, described her as the Woman of the Apocalypse from the New Testament's Revelation 12:1, "clothed with the sun, and the moon under her feet, and upon her head a crown of twelve stars." She is described as a representation of the Immaculate Conception.[58]

Virgil Elizondo says the image also had layers of meaning for the indigenous people of Mexico who associated her image with their polytheistic deities, which further contributed to her popularity.[83][84] Her blue-green mantle was the color reserved for the divine couple Ometecuhtli and Omecihuatl;[85] her belt is interpreted as a sign of pregnancy; and a cross-shaped image, symbolizing the cosmos and called nahui-ollin, is inscribed beneath the image's sash.[86] She was called "mother of maguey,"[87] the source of the sacred beverage pulque.[88] Pulque was also known as "the milk of the Virgin."[89] The rays of light surrounding her are seen to also represent maguey spines.[87]

Cultural significance

Juan Diego's tilma has become Mexico's most popular religious and cultural symbol, and has received widespread ecclesiastical and popular veneration. In the 19th century it became the rallying cry of the Spaniards born in America, in what they denominated 'New Spain'. They said they considered the apparitions as legitimizing their own indigenous Mexican origin. They infused it with an almost messianic sense of mission and identity, thereby also justifying their armed rebellion against Spain.[90][91]

Symbol of Mexico

Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe became a recognized symbol of Catholic Mexicans. Miguel Sánchez, the author in 1648 of the first published account of the vision, identified Guadalupe as Revelation's Woman of the Apocalypse, and said:

... this New World has been won and conquered by the hand of the Virgin Mary ... [who had] prepared, disposed, and contrived her exquisite likeness in this, her Mexican land, which was conquered for such a glorious purpose, won that there should appear so Mexican an image.[58]

Throughout the Mexican national history of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Guadalupan name and image have been unifying national symbols; the first President of Mexico (1824–1829) changed his name from José Miguel Ramón Adaucto Fernández y Félix to Guadalupe Victoria in honor of the Virgin of Guadalupe.[92] Father Miguel Hidalgo, in the Mexican War of Independence (1810), and Emiliano Zapata, in the Mexican Revolution (1910), led their respective armed forces with Guadalupan flags emblazoned with an image of Our Lady of Guadalupe.[93] In 1999, the Church officially proclaimed her the Patroness of the Americas, the Empress of Latin America, and the Protectress of Unborn Children.

In 1810, Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla initiated the bid for Mexican independence with his Grito de Dolores, with the cry "Death to the Spaniards and long live the Virgin of Guadalupe!" When Hidalgo's mestizo-indigenous army attacked Guanajuato and Valladolid, they placed "the image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, which was the insignia of their enterprise, on sticks or on reeds painted different colors" and "they all wore a print of the Virgin on their hats."[92] After Hidalgo's death, leadership of the revolution fell to a mestizo priest named José María Morelos, who led insurgent troops in the Mexican south. Morelos adopted the Virgin as the seal of his Congress of Chilpancingo, inscribing her feast day into the Chilpancingo constitution and declaring that Guadalupe was the power behind his victories:

New Spain puts less faith in its own efforts than in the power of God and the intercession of its Blessed Mother, who appeared within the precincts of Tepeyac as the miraculous image of Guadalupe that had come to comfort us, defend us, visibly be our protection.[92]

Simón Bolívar noticed the Guadalupan theme in these uprisings, and shortly before Morelos's execution in 1815 wrote: "the leaders of the independence struggle have put fanaticism to use by proclaiming the famous Virgin of Guadalupe as the queen of the patriots, praying to her in times of hardship and displaying her on their flags... the veneration for this image in Mexico far exceeds the greatest reverence that the shrewdest prophet might inspire."[58]

In 1912, Emiliano Zapata's peasant army rose out of the south against the government of Francisco Madero. Though Zapata's rebel forces were primarily interested in land reform—"tierra y libertad" ('land and liberty') was the slogan of the uprising—when his peasant troops penetrated Mexico City, they carried Guadalupan banners.[94] More recently, the contemporary Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) named their "mobile city" in honor of the Virgin: it is called Guadalupe Tepeyac. EZLN spokesperson Subcomandante Marcos wrote a humorous letter in 1995 describing the EZLN bickering over what to do with a Guadalupe statue they had received as a gift.[95]

Mexican culture

Harringon argues that: The Aztecs... had an elaborate, coherent symbolic system for making sense of their lives. When this was destroyed by the Spaniards, something new was needed to fill the void and make sense of New Spain ... the image of Guadalupe served that purpose.[96]

Hernán Cortés, the Conquistador who overthrew the Aztec Empire in 1521, was a native of Extremadura, home to Our Lady of Guadalupe. By the 16th century, the Extremadura Guadalupe, a statue of the Virgin said to be carved by Luke the Evangelist, was already a national icon. It was found at the beginning of the 14th century, when the Virgin appeared to a humble shepherd and ordered him to dig at the site of the apparition. The recovered Virgin then miraculously helped to expel the Moors from Spain, and her small shrine evolved into the great Guadalupe monastery.

According to the traditional account, the name of Guadalupe, as the name was heard or understood by Spaniards, was chosen by the Virgin herself when she appeared on the hill outside Mexico City in 1531, ten years after the Conquest.[97]

Guadalupe continues to be a mixture of the cultures which blended to form Mexico, both racially and religiously,[98] "the first mestiza",[99] or "the first Mexican",[100] "bringing together people of distinct cultural heritages, while at the same time affirming their distinctness."[101] As Jacques Lafaye wrote in Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe, "as the Christians built their first churches with the rubble and the columns of the ancient pagan temples, so they often borrowed pagan customs for their own cult purposes."[102] The author Judy King asserts that Guadalupe is a "common denominator" uniting Mexicans. Writing that Mexico is composed of a vast patchwork of differences—linguistic, ethnic, and class-based—King says "The Virgin of Guadalupe is the rubber band that binds this disparate nation into a whole."[100] The Mexican novelist, Carlos Fuentes, once said that "you cannot truly be considered a Mexican unless you believe in the Virgin of Guadalupe."[103] Nobel Literature laureate Octavio Paz wrote in 1974 that "The Mexican people, after more than two centuries of experiments and defeats, have faith only in the Virgin of Guadalupe and the National Lottery."[104]

In literature and film

One notable reference in literature to the image and its alleged predecessor, the Aztec Earth goddess Tonantzin, is in Sandra Cisneros' short story "Little Miracles, Kept Promises", from her collection Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (1991). Cisneros' story is constructed out of brief notes that people give Our Lady of Guadalupe in thanks for favors received, which in Cisneros' hands becomes a portrait of an extended Chicano community living throughout Texas. "Little Miracles" ends with an extended narrative (pp. 124–129) of a feminist artist, Rosario "Chayo" de León, who at first didn't allow images of La Virgen de Guadalupe in her home because she associated her with subservience and suffering, particularly by Mexican women. But when she learns that Guadalupe's shrine is built on the same hill in Mexico City that had a shrine to Tonantzin, the Aztec Earth goddess and serpent destroyer, Chayo comes to understand that there's a deep, syncretic connection between the Aztec goddess and the Mexican saint; together they inspire Chayo's new artistic creativity, inner strength, and independence. In Chayo's words, "I finally understood who you are. No longer Mary the mild, but our mother Tonantzin. Your church at Tepeyac built on the site of her temple" (128).[105]

The image and its alleged apparition was investigated several times, including in the 2013 documentary The Blood & The Rose, directed by Tim Watkins.[106] Documentarians have been portraying the message of Our Lady of Guadalupe since the 1990s, in an attempt to bring the message of the apparition to the North American audience.

Pious beliefs and devotions

Protection from damage

Catholic sources attest that the original image has many miraculous and supernatural properties, including that the tilma has maintained its structural integrity for approximately 500 years despite exposure to soot, candle wax, incense, constant manual veneration by devotees, the historical fact that the image was displayed without any protective glass for its first 115 years, while replicas normally endure for only circa 15 years before degrading,[107] and that it repaired itself with no external assistance after a 1791 accident in which nitric acid was spilled on its top right, causing considerable damage but leaving the aureola of the Virgin intact.

Furthermore, on November 14, 1921, a bomb hidden within a basket of flowers and left under the tilma by an anti-Catholic secularist exploded and damaged the altar of the Basilica that houses the original image, but the tilma was unharmed. A brass standing crucifix, bent by the explosion, is now preserved at the shrine's museum and is believed to be miraculous by devotees.[108][109]

Other alleged supernatural qualities

In 1929 and 1951 photographers said they found a figure reflected in the Virgin's eyes; upon inspection they said that the reflection was tripled in what is called the Purkinje effect, commonly found in human eyes.[110] An ophthalmologist, Dr. Jose Aste Tonsmann, later enlarged an image of the Virgin's eyes by 2500x and said he found not only the aforementioned single figure, but images of all the witnesses present when the tilma was first revealed before Zumárraga in 1531, plus a small family group of mother, father, and a group of children, in the center of the Virgin's eyes, fourteen people in all (including a young Black girl, representing Zumárraga's slave whom he freed in his will).[111][112]

In 1936 biochemist Richard Kuhn reportedly analyzed a sample of the fabric and announced that the pigments used were from no known source, whether animal, mineral, or vegetable.[111] According to The Wonder of Guadalupe by Francis Johnston, this was requested by Professor Hahn and Professor Marcelino Junco, retired professor of organic chemistry at the National University of Mexico. This has been taken as further evidence of the tilma's miraculous nature. In late 2019, investigators from The Higher Institute of Guadalupano Studies concluded that there was no evidence Kuhn ever investigated the Lady of Guadalupe or made the statement attributed to him.[113]

Dr. Philip Serna Callahan, who photographed the icon under infrared light, declared from his photographs that portions of the face, hands, robe, and mantle had been painted in one step, with no sketches or corrections and no visible brush strokes.[114]

Veneration

The shrine of the Virgin of Guadalupe is the most visited Catholic pilgrimage destination in the world. Over the Friday and Saturday of December 11 to 12, 2009, a record number of 6.1 million pilgrims visited the Basilica of Guadalupe in Mexico City to commemorate the anniversary of the apparition.[115]

The Virgin of Guadalupe is considered the Patroness of Mexico and the Continental Americas; she is also venerated by Native Americans, on the account of the devotion calling for the conversion of the Americas.[116] Replicas of the tilma can be found in thousands of churches throughout the world, and numerous parishes bear her name.

Due to Mary's appearance as a pregnant mother and her claims as mother of all in the apparition, the Blessed Virgin Mary, under this title is popularly invoked as Patroness of the Unborn and a common image for the Pro-Life movement.[117][118][119]

See also

- Acheiropoieta

- Cathedral of Our Lady of Guadalupe

- Lord of Miracles of Buga

- Mariology

- Miracle of the roses

- Codex Cumanicus

- Huei tlamahuiçoltica

References

- "World's Most-Visited Sacred Sites", Travel and Leisure, January 2012

- ""Shrine of Guadalupe Most Popular in the World", Zenit, June 13, 1999". Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2009.

- English translation of the Nican Mopohua, a 17th-century account written in the native Nahuatl language.

- Sousa, Lisa; Poole, Stafford; Lockhart, James (1998). The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's Huei tlamahuiçoltica of 1649. UCLA Latin American studies, vol. 84; Nahuatl studies series, no. 5. Stanford & Los Angeles, California: Stanford University Press, UCLA Latin American Center Publications. p. 65. ISBN 0-8047-3482-8. OCLC 39455844.

- This apparition is somewhat elided in the Nican Mopohua but is implicit in three brief passages (Sousa et al., pp. 75, 77, 83). It is fully described in the Imagen de la Virgen María of Miguel Sánchez published in 1648.

- The date does not appear in the Nican Mopohua, but in Sanchez's Imagen.

- The procession and miracle are not part of the Nican Mopohua proper, yet introduce the Nican Mopectana that immediately follows the Nican Mopohua in the Huei Tlamahuiçoltica.

- Pope Pius X (June 16, 1910). "Gratiae, quae" (in Latin). Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- "Virgen de Guadalupe". Mariologia.org. Archived from the original on April 26, 2012. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- Pope Pius XI (July 16, 1935). Acta Apostolicae Sedis (PDF) (in Latin). Vol. XXVIII. pp. 63–64. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- Pope Pius XII (September 12, 1942). Acta Apostolicae Sedis (PDF) (in Latin). Vol. XXXIV. pp. 336–337. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- Pope Pius XII (July 16, 1958). Acta Apostolicae Sedis (PDF) (in Latin). Vol. LI. p. 32. Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- Pope Pius XII (October 12, 1945). "Radiomensaje de Su Santidad Pío XII a los fieles mexicanos en el 50 aniversario de la coronación canónica de la Virgen de Guadalupe" [Radio message of His Holiness Pius XII to the Mexican faithful on the 50th anniversary of the canonical coronation of the Virgin of Guadalupe] (in Spanish). Retrieved March 20, 2022.

- Pope Paul VI (May 31, 1966). "Radiomensaje del Santo Padre Pablo VI con motivo de la entrega de la Rosa de Oro a la Basílica de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe" [Radio message of the Holy Father Paul VI on the occasion of the presentation of the Golden Rose to the Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe] (in Spanish). Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- "Pope Francis sends golden rose to Our Lady of Guadalupe". Catholic News Agency. November 22, 2013. Retrieved March 25, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - "La Virgen del Agostadero en Villa García, Zacatecas". turimexico.com (in Spanish). August 26, 2016. Retrieved December 21, 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - Dysinger, Luke. "The Virgin Mary in Art", St. John's Seminary, Camarillo

- "Our Lady of Guadalupe in Spain", Our Lady in the Old World and New, Medieval Southwest, Texas Tech University

- Castaño, Victor Manuel: coordinador general, "Estudio físico-químico y técnico del códice 1548", Colección Privada Herdez (1997); Ciencia Hoy, "La detectivesca ciencia de los documentos antiguos: el caso de códice 1548", (a) 29 April, (b) 6 May, and (c) 13 May 2008

- "Códice 1548 o "Escalada"" (in Spanish). Inigne y Nacional Basílica de Santa María de Guadalupe. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015.

- Peralta, Alberto (2003). "El Códice 1548: Crítica a una supuesta fuente Guadalupana del Siglo XVI". Artículos (in Spanish). Proyecto Guadalupe. Archived from the original on February 9, 2007. Retrieved December 1, 2006., Poole, Stafford (July 2005). "History vs. Juan Diego". The Americas. 62: 1–16. doi:10.1353/tam.2005.0133. S2CID 144263333., Poole, Stafford (2006). The Guadalupan Controversies in Mexico. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-5252-7. OCLC 64427328.

- D. Brading (2001), Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries, Cambridge University Press, pp. 117–118, cf. p. 359.

- León-Portilla, Miguel; Antonio Valeriano (2000). Tonantzin Guadalupe : pensamiento náhuatl y mensaje cristiano en el "Nicān mopōhua" (in Spanish). Mexico: Colegio Nacional: Fondo de Cultura Económico. ISBN 968-16-6209-1.

- Burrus S. J., Ernest J. (1981). "The Oldest Copy of the Nican Mopohua". Cara Studies in Popular Devotion. Washington D.C.: Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate (Georgetown University). II, Guadalupan Studies (4). OCLC 9593292.

- O'Gorman, Edmundo (1991). Destierro de sombras : luz en el origen de la imagen y culto de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe del Tepeyac (in Spanish). Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. ISBN 968-837-870-4.

- Robert Ricard, The Spiritual Conquest of Mexico. Translated by Lesley Byrd Simpson. Berkeley: University of California Press 1966, p. 188.

- de la Torre Villar, Ernesto; Navarro de Anda, Ramiro (2007). Nuevos testimonios históricos guadalupanos. México, D.F.: Fondo de Cultura Económica. p. 1448. ISBN 978-968-16-7551-6. Retrieved May 25, 2013.

- Ricard, Spiritual Conquest, p. 189.

- Poole 1995, p. 60.

- Poole 1995, pp. 60–62.

- Dunning, Brian (April 13, 2010). "Skeptoid #201: The Virgin of Guadalupe". Skeptoid. Retrieved June 22, 2017.

- J. Nickell, "Image of Guadalupe: myth – perception". Skeptical Inquirer 21:1 (January/ February 1997), p. 9.

- Jody Brant Smith, The image of Guadalupe, Mercer University Press, 1994, p. 73.

- Francis Johnston, The Wonder of Guadalupe, TAN Books, 1981, p. 47

- Ricard, Spiritual Conquest, p. 190.

- Bernardino de Sahagún, Florentine Codex: Introduction and Indices, Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble, translators. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1982, p. 90.

- L. Burkhart (2001). Before Guadalupe: the Virgin Mary in early colonial Nahuatl literature. Austin: University of Texas Press.

- D. A. Brading, Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe, (Cambridge University Press, 2001) p. 5

- "Insigne y Nacional Basílica de Santa María de Guadalupe". basilica.mxv.mx. Retrieved December 5, 2017.

- Sousa, Lisa; Poole, Stafford; Lockhart, James (1998). The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's Huei tlamahuiçoltica of 1649. UCLA Latin American studies, vol. 84; Nahuatl studies series, no. 5. Stanford & Los Angeles, California: Stanford University Press, UCLA Latin American Center Publications. pp. 42–47. ISBN 0-8047-3482-8. OCLC 39455844.

- Story of the manuscript, as was told by Thomas Lannon, assistant curator of the New York Public Library. A digital scan of the manuscript is available here.

- Brading, p. 344

- Treviño, Eduardo Chávez; translated from Spanish by Carmen; Montaño, Veronica (2006). Our Lady of Guadalupe and Saint Juan Diego : the historical evidence. Lanham, Md.: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 121 of 212. ISBN 0742551059.

- Anales de Juan Bautista Folio 6r

- Cartas Sobre la Tradición de Ntra. Sra. de Guadalupe de México, Servando Teresa De Mier 1797 p. 53

- Vera, Fortino Hipólito (1889). Informaciones sobre la milagrosa aparicion de la santisima Virgin de Guadalupe, recibidas en 1666 y 1723 (in Spanish). OCLC 682107928.[page needed]

- Guadalupe; Informaciones jurídicas de 1666 Archived December 8, 2015, at the Wayback Machine

- "Informaciones de 1666". Archived from the original on January 5, 2016. Retrieved December 8, 2015.

- "Vicaría de Guadalupe. Antecedentes históricos. Antigua Basílica de Santa María de Guadalupe". Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved November 17, 2021.

- "Virgen de Guadalupe con las cuatro apariciones y una vista del Santuario de Tepeyac". Google Arts & Culture.

- Stafford Poole, The Guadalupan Controversies in Mexico, Stanford University Press, 2006, p. 60

- Brading (2002), Mexican Phoenix, p. 307

- Enciclopedia Guadalupana, p. 267 (vol. II)

- Britannica.com

- Saragoza, Alex (2012). Mexico Today: An Encyclopedia of Life in the Republic. ABC-CLIO. p. 95. ISBN 978-0-313-34948-5.

- Daily Catholic Archived October 16, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, December 7, 1999, accessed November 30, 2006

- Juan Diego y las Apariciones el pimo Tepeyac (Paperback) by Joaquín García Icazbalceta ISBN 970-92771-3-8

- D.A. Brading, Mexican Phoenix Our Lady of Guadalupe:Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries (2001) p. 58

- "Nican Mopohua: Here It Is Told," Archived November 21, 2011, at the Wayback Machine, p. 208, UC San Diego

- Anderson Carl and Chavez Eduardo, Our Lady of Guadalupe: Mother of the Civilization of Love, Doubleday, New York, 2009, p. 205

- González, Ondina E. and Justo L. González, Christianity in Latin America: A History, p. 59, Cambridge University Press, 2008

- See Callahan Philip Serna, The Tilma under Infrared Radiation, CARA Studies on Popular Devotion, vol. II: Guadalupanan Studies No. 3, pp. 6–16

- Callahan, Philip Serna, The Tilma under Infrared Radiation, CARA Studies on Popular Devotion, vol. II: Guadalupanan Studies No. 3, p. 16.

- For a brief description of the vault, see Callahan, Philip Serna, The Tilma under Infrared Radiation, CARA Studies on Popular Devotion, vol. II: Guadalupanan Studies No. 3, at p. 6

- See Enciclopedia Guadalupana, p. 267 (vol. 2).

- See Enciclopedia Guadalupana, pp. 536f. (vol. 3). The December 2001 issue (special edition) of Guia México Desconocido (p. 86) dedicated to the Virgen de Guadalupe has a fact box on p. 21 which gives slightly different dimensions: height 178 by 103 cm wide (70 by 41 in).

- See Fernández de Echeverría y Veytia (1718–1780), Baluartes de México, (published posthumously, 1820), p. 32.

- Cabrera, Miguel: Maravilla Americana y conjunto de varias maravillas observadas con la direccíon de las reglas del arte de la pintura en la prodigiosa imagen de Nuestra Señora de Guadalupe, Mexico, 1756, facs. ed. Mexico, 1977

- Brading, D.A.: Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries, Cambridge University Press, 2001, pp. 169–172

- Vera, Rodrigo (July 27, 2002). "Un restaurador de la guadalupana expone detalles técnicos que desmitifican a la imagen". Proceso. No. 1343.

- Callahan, Philip S. (1981). The Tilma Under Infra-red Radiation: An Infrared and Artistic Analysis of the Image of the Virgin Mary in the Basilica of Guadalupe. Center for Applied Research in the Apostolate. OCLC 11200397.[page needed]

- Leatham, Miguel (1989). "Indigenista Hermeneutics and the Historical Meaning of Our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico". Folklore Forum. 22 (1/2): 27–39. hdl:2022/2068.

- Vera, Rodrigo (May 19, 2002). "El análisis que ocultó el Vaticano". Proceso. No. 1333.

- http://foro.univision.com/t5/Testigos-de-Jehov%C3%A1/SE-DEMUESTRA-QUE-LA-IMAGEN-DE-LA-V-DE-GUADALUPE-ES-DE-OBRA/m-p/217920440%5B%5D

- "manos humanas pintaron la guadalupana"[permanent dead link]

- Brading (2001), Mexican Phoenix, p. 170

- Bomford, David; Roy, Ashok; Smith, Alistair (1986). "The Techniques of Dieric Bouts: Two Paintings Contrasted". National Gallery Technical Bulletin. 10.

- Santos Gómez, Sonia; San Andrés Moya, Margarita (March 30, 2004). "La pintura de sargas". Archivo Español de Arte. 77 (305): 59–74. doi:10.3989/aearte.2004.v77.i305.256.

- Doherty, T., & Woollett, A. T. (2009). Looking at paintings: a guide to technical terms. Getty Publications.[page needed]

- Johnson, Maxwell E. (2015). The Church in Act: Lutheran Liturgical Theology in Ecumenical Conversation. Fortress Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-1451496680.

- "Jesse Brandow: Missionary to Guatemala and Mexico". www.facebook.com. Retrieved January 3, 2019.

- McMenamin, M. (2006). "Our Lady of Guadalupe and Eucharistic Adoration". Numismatics International Bulletin. 41 (5): 91–97.

- Elizondo, Virgil. Guadalupe, Mother of a New Creation. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1997

- "A short history of Tonantzin, Our Lady of Guadalupe". Indian Country News. Archived from the original on March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 4, 2019.

- UTPA.edu, "La Virgen de Guadalupe", accessed November 30, 2006

- Tonantzin Guadalupe, by Joaquín Flores Segura, Editorial Progreso, 1997, ISBN 970-641-145-3, 978-970-641-145-7, pp. 66–77

- Taylor, William B. (1979). Drinking, Homicide, and Rebellion in Colonial Mexican Villages. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804711128.

- "What is Pulque?". Del Maguey: Single Village Mezcal. Archived from the original on October 16, 2020. Retrieved October 13, 2020.

- Bushnell, John (1958). "La Virgen de Guadalupe as Surrogate Mother in San Juan Aztingo". American Anthropologist. 60 (2): 261. doi:10.1525/aa.1958.60.2.02a00050.

- Poole, Stafford. Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797 (1995)

- Taylor, William B., Shrines and Miraculous Images: Religious Life in Mexico Before the Reforma (2011)

- Krauze, Enrique. Mexico, Biography of Power. A History of Modern Mexico 1810–1996. HarperCollins: New York, 1997.

- Galeano, Eduardo (January 1997). Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent. p. 46. ISBN 978-0853459910.

- Documentary footage of Zapata and Pancho Villa's armies entering Mexico City can be seen at YouTube.com, Zapata's men can be seen carrying the flag of the Guadalupana about 38 seconds in.

- Subcomandante Marcos, Flag.blackened.net, "Zapatistas Guadalupanos and the Virgin of Guadalupe" March 24, 1995, accessed December 11, 2006.

- Harrington, Patricia (1988). "Mother of Death, Mother of Rebirth: The Mexican Virgin of Guadalupe". Journal of the American Academy of Religion. 56 (1): 25–50. doi:10.1093/jaarel/LVI.1.25. JSTOR 1464830.

- Sancta.org Archived October 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, "Why the name 'of Guadalupe'?", accessed November 30, 2006

- Elizondo, Virgil. AmericanCatholic.org Archived October 26, 2007, at the Wayback Machine, "Our Lady of Guadalupe. A Guide for the New Millennium" St. Anthony Messenger Magazine Online. December 1999; accessed December 3, 2006.

- Lopez, Lydia. "'Undocumented Virgin.' Guadalupe Narrative Crosses Borders for New Understanding." Episcopal News Service. December 10, 2004.

- King, Judy (May 29, 2020). "La Virgen de Guadalupe - Mother of all Mexico". MexConnect.

- O'Connor, Mary (1989). "The Virgin of Guadalupe and the Economics of Symbolic Behavior". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 28 (2): 105–119. doi:10.2307/1387053. JSTOR 1387053.

- Lafaye, Jacques. Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe. The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 1976

- Demarest, Donald. "Guadalupe Cult ... In the Lives of Mexicans." p. 114 in A Handbook on Guadalupe, Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate, eds. Waite Park MN: Park Press Inc, 1996

- Paz, Octavio (1987). "Foreword". In Lafaye, Jacques (ed.). Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1531–1813. University of Chicago Press. pp. ix–xxii. ISBN 978-0-226-46788-7.

- Cisneros, Sandra. "Little Miracles, Kept Promises." Woman Hollering Creed and Other Stories. New York: Random House, 1991. 116–129.

- The Blood & the Rose at IMDb

- Guerra, Giulio Dante (1992). "La Madonna di Guadalupe: un caso di 'inculturazione' miracolosa". Cristianità. No. 205–206.

- Brading, D. A. (2001). Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition Across Five Centuries. Cambridge University Press. p. 314. ISBN 978-0-521-53160-3.

- Poole, Stafford (2006). The Guadalupan Controversies in Mexico. Stanford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 978-0-8047-5252-7.

- https://web.archive.org/web/20071209175102/http://www.interlupe.com.mx/8-e.html Web.archive.org][unreliable source?]. "The Eyes" Interlupe. Accessed December 3

- "Science Sees What Mary Saw From Juan Diego's Tilma", catholiceducation.org Archived June 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- "Our Lady's eyes". www.messengersaintanthony.com. September 30, 2016. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- "Investigación en Documentos del Dr. Richard Khun en Alemania". Morenita. Archived from the original on October 24, 2020. Retrieved October 14, 2020.

- Sennott, Br. Thomas Mary. MotherOfAllPeoples.com Archived June 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, "The Tilma of Guadalupe: A Scientific Analysis".

- Znit.org Archived November 13, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "Our Lady of Guadalupe | Description, History, & Facts | Britannica".

- "The Patroness of the Unborn: Our Lady of Guadalupe". Human Life International. December 13, 2012. Retrieved November 28, 2021.

- "Knots in Mary's Garments : University of Dayton, Ohio".

- "Goan Churches | Information on all Churches in Goa".

- Pure gold does not react with nitric acid, though pure gold does react with aqua regia, a mixture of concentrated nitric acid and hydrochloric acid.

Works cited

- Poole, Stafford (1995). Our Lady of Guadalupe: The Origins and Sources of a Mexican National Symbol, 1531–1797. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

Further reading

Primary sources

- Cabrera, Miguel, Maravilla americana y conjunto de raras maravillas ... en la prodigiosa imagen de Nuestra Srs. de Guadalupe de México (1756). Facsimile edition, Mexico City: Editorial Jus 1977.

- Cayetano de Cabrera y Quintero, Escudo de armas de México: Celestial protección de esta nobilissima ciudad de la Nueva-España Ma. Santissima en su portentosa imagen del Mexico Guadalupe. Mexico City: Impreso por la Viuda de don Joseph Bernardo de Hogal 1746.

- The Story of Guadalupe: Luis Laso de la Vega's "Huei tlmahuiçoltica" of 1649. edited and translated by Lisa Sousa, Stafford Poole, and James Lockhart. Vol. 84 of UCLA Latin American Center Publications. Stanford: Stanford University Press 1998.

- Noguez, Xavier. Documentos Guadalupanos. Mexico City: El Colegio Mexiquense and Fondo de Cultura Económia 1993.

Secondary sources

- Sister Mary Amatora, O.S.F.. The Queen's Portrait: The Story of Guadalupe (1961, 1972) ISBN 0682474681 (Hardcover) ISBN 0682474797 (Paperback) (Hymn To Our Lady Of Guadalupe p. 118.)

- Brading, D.A., Mexican Phoenix: Our Lady of Guadalupe: Image and Tradition across Five Centuries. New York: Cambridge University Press 2001.

- Burkhart, Louise. "The Cult of the Virgin of Guadalupe in Mexico" in South and Meso-American Native Spirituality, ed. Gary H. Gossen and Miguel León-Portilla, pp. 198–227. New York: Crossroad Press 1993.

- Burkhart, Louise. Before Guadalupe: The Virgin Mary in Early Colonial Nahuatl Literature. Albany: Institute for Mesoamerican Studies and the University of Texas Press 2001.

- Cline, Sarah (August 1, 2015). "Guadalupe and the Castas". Mexican Studies/Estudios Mexicanos. 31 (2): 218–247. doi:10.1525/mex.2015.31.2.218.

- Deutsch, James (December 11, 2017). "A New Way to Show Your Devotion in Mexico City: Wear a T-Shirt". Smithsonian Magazine.

- Elizondo, Virgil. Guadalupe, Mother of a New Creation. Maryknoll, New York: Orbis Books, 1997

- Lafaye, Jacques. Quetzalcoatl and Guadalupe: The Formation of Mexican National Consciousness, 1532–1815. Trans. Benjamin Keen. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1976.

- Maza, Francisco de la. El Guadalupismo mexicano. Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Económica 1953, 1981.

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot (December 1992). "The Virgin of Guadalupe: Symbol of Conquest or Liberation?". Art Journal. 51 (4): 39–47. doi:10.1080/00043249.1992.10791596. ProQuest 223311874.

- Peterson, Jeanette Favrot. Visualizing Guadalupe: From Black Madonna to Queen of the Americas. Austin: University of Texas Press 2014.

- Poole, Stafford (July 2005). "History Versus Juan Diego". The Americas. 62 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1353/tam.2005.0133. S2CID 144263333.

- Sánchez, David A. (2008). From Patmos to the Barrio: Subverting Imperial Myths. Fortress Press. ISBN 978-1-4514-0589-7.

- Taylor, William B. (February 1987). "The Virgin of Guadalupe in New Spain: an inquiry into the social history of Marian devotion". American Ethnologist. 14 (1): 9–33. doi:10.1525/ae.1987.14.1.02a00020. JSTOR 645631.

External links

- Lady of Guadalupe film, Directed by Pedro Brenner, 2021

- NEWS.BBC.co.uk, BBC photo essay of December 12 festivities in San Miguel de Allende, Gto.

- "Shrine of Guadalupe" on the Catholic Encyclopedia

Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии