art.wikisort.org - Artist

Aydin Aghdashloo (Persian: آیدین آغداشلو; born October 30, 1940) is an Iranian painter, graphist, art curator, writer, and film critic.[1]

Aydin Aghdashloo | |

|---|---|

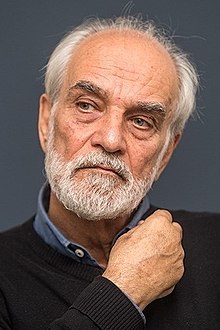

Aghdashloo in 2014 | |

| Born | Aydin Aghdashloo October 30, 1940 Rasht, Iran |

| Other names | Faramarz Kheybari |

| Education | Tehran University |

| Occupation |

|

Works | Termination Memories Falling Angels Identity: In Praise of Sandro Botticelli |

| Spouse(s) | Shohreh Aghdashloo

(m. 1972; div. 1980)Firouzeh "Fay" Athari

(m. 1981, divorced) |

| Children | 2, including Tara |

| Honours | Legion of Honour |

| Website | aghdashloo |

Early life and education

Aydin Aghdashloo, the son of Mohammad-Beik Aghdashloo (Haji Ouf) and Nahid Nakhjevan,[2] was born on October 30, 1940, in the Afakhray neighborhood of Rasht.[3] His father was a Azerbaijani Turk and a member of Azerbaijan Equality Party and his family assumes their surname from the small town of Agdash.[4] After seeing Aydin's talent in painting at school and his hand-made models, Mohammad-Beik took him to Habib Mohammadi, a painter and a teacher from Rasht.

In 1959, at the age of 19, after successfully passing the university entrance examination, he enrolled at Tehran University's School of Fine Arts. In 1967, unable to complete his studies after eight years, he dropped out of college.[citation needed]

Works

In 1975, Aghdashloo held his first individual exhibition at Iran-America Society in Tehran. The exhibited paintings were mostly about floating things, dolls and some works about the Renaissance. Between 1976 and 1979, Aghdashloo helped open and launch Museums Abghineh va Sofalineh, Reza Abbasi Museum and Contemporary Arts in Tehran and also Kerman and Khorram-Abad Museums.[3]

Aghdashloo was the holder and coordinator of several exhibitions after the Iranian revolution. While none of them were special exhibitions of his works, they played an important role in introducing contemporary Iranian art to the people inside and outside Iran. He took multiple exhibitions from Iran to other countries, including "Iranian Art, since the Past until Today" in China, "Past Iranian Art" in Japan, and the contemporary Iranian paintings with a traditional background sent to Bologna, Italy.[4] Aghdashloo is also a recipient of the Legion of Honour.[5]

Aghdashloo's interest in including surreal spaces in his works and painting floating objects began in his 30 years of age. During the period, his works were of floating objects having a shadow on the ground. In a surrealistic environment, he painted dolls having no faces influenced by Gergeo Deki Riko and they later became a large part of his series "Years of Fire and Snow". According to him, painting of such faceless dolls helped him say the subconscious suspicious and illusive word in the form of a painting.[6]

After the 1979 revolution and the eight-year war, most of Aghdashloo's works were about memorials and objects proceeding to doom and damage; abandoned huts and views, green wooden rotten windows with broken glasses, old doors with rusted locks, and deadly blades as symbols of missiles hitting the cities; all of them showed the painter's thinking of gradual doom and damage as the passing of hard times. Using Iranian miniature continued in his works and he used every Iranian classic style and space for transferring his subjective concepts about the contemporary world.

Aghdashloo paints most of his works by gouache on canvas.

Bahram Beyzai writes in a part of his article: "Why shouldn't I be rude and say that if there's a value in copy-painting, the patterns of the previous celebrities of painting and visualizing aren't in our reach; so that as evaluation criteria, they can testify for the level of accomplishment of those masters in copy-painting; but their works, which Aydin has remade, are a proof of Aydin's skill in copy-painting. It's obvious that copy-painting wasn't all of their art, as it's not all of Aydin's. It's Aydin's imagination and time-sighting and death-aware thought that's the final maker of his work. The crevices that time has made in the paintings, and the oppressions that the cosmos – or man's hand – has inflicted upon them. In Aydin's repaintings, these masters' praise are accompanied with sorrow for their own and their works' mortality."[7]

In a ceremony that was held in French embassy in Iran on Tuesday, January 12, 2016, Aghdashloo received the Legion of Honour.[5]

Controversy

Allegations of sexual misconduct

On August 22, 2020, Sara Omatali, a former reporter publicly stated that during an encounter in late 2006, Aydin Aghdashloo forcibly grabbed her and kissed her in his office, where they had met for an interview.[8][9] On August 27, 2020, Aghdashloo issued English and Persian public statements denying the allegations and expressing his support for women's movements, stating that false accusations made it difficult for real victims to seek justice.[10]

Barbad Golshiri, son of Iranian author Houshang Golshiri, announced that the new edition of his father's novel, Prince Ehtejab, would not include Aghdashloo's painting.[11] Bahman Kiarostami, documentary filmmaker and son of the acclaimed filmmaker, Abbas Kiarostami, defended Golshiri's action as a "declaration of support for a social movement", and a legal verdict was irrelevant "because of the obvious: in the words of Leonard Cohen and Asghar Farhadi, 'everybody knows'." Aghdashloo's behaviour, Kiarostami added, was no longer tolerable "in the face of a mass social movement."[12]

Fahime Khezr Heidari, a journalist based in Washington, D.C., said Omatali was "one of the most ethical people" she knew and added that she had heard a "dozen" similar cases against Aghdashloo.[13] Laleh Sabouri, a former Iranian film and television actress tweeted that she was a student of Aghdashloo's for two years in the early 1990s and though she was never subjected to Aghdashloo's sexual misconducts, yet she could confirm that sexual misconducts appeared to be a natural part of Aghdashloo's life.[14][15]

Investigation in The New York Times

On October 22, 2020, Farnaz Fassihi published two months worth of investigations, interviewing alleged victims of Aghdashloo in The New York Times.[9] The investigation included 13 women who accused Aghdashloo of sexual abuse, including one who was underage. The report documented victims comparing Aghdashloo to Harvey Weinstein:

Nineteen described him as the "Harvey Weinstein of Iran," elevating or destroying careers of women depending on their receptiveness to his advances. One former student said he had offered her one of his paintings – worth $100,000, the price of a small apartment in Tehran – if she slept with him. Another said he had retaliated when she refused him, telling galleries to shun her artwork. Her career faltered.[9]

Personal life

He was previously married to architect Firouzeh "Fay" Athari in 1981. Together they had two children, Takin and Tara Aghdashloo.[16][17][18] From 1972 until 1980, his first marriage was to actress Shohreh Aghdashloo (née Vaziri-Tabar), and they did not have children.[19]

See also

- List of Iranian painters

References

- "BBC فارسی - فرهنگ و هنر - از دور و نزدیک؛ نگاهی به نوشتههای سینمایی آیدین آغداشلو". bbc.com (in Persian). Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Bayzai, Bahram. About Aydin Aghdashloo and His Art.

- Maskub, Taraneh. The Calendar of Aydin Aghdashloo's Life.

- Karimian, Rambod (1993). "An Interview with Aydin Aghdashloo". Kalak.

- "آیدین آغداشلو، نقاش ایرانی، نشان شوالیه فرانسه را دریافت کرد". BBC News فارسی (in Persian). January 13, 2016. Retrieved October 24, 2020.

- Murizinezhad, Hasan. Contemporary Iranian Artists: Aydin Aghdashloo.

- Beyzai. About Aydin Aghdashloo and His Art.

- Alinejad, Masih; Hakakian, Roya (August 26, 2020). "Iranian women are staging an offensive against sexual abuse. It's long overdue". The Washington Post.

- Fassihi, Farnaz (October 23, 2020). "A #MeToo Awakening Stirs in Iran". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved October 23, 2020.

- "Posts [@aydin_aghdashloo Instagram profile]". August 27, 2020. Retrieved August 27, 2020.

- "Aghdashloo design removed from Prince Ehtejab cover, after being accused of "sexual harassment"". Aznews TV. August 30, 2020.

- "آیا کسی ادعای فمینیست بودن تارا آغداشلو را باور خواهد کرد؟". August 31, 2020.

- "Iran's #MeToo Moment: First Steps of a "Long March"". IranWire | خانه. Retrieved September 1, 2020.

- "Faces: Laleh Sabouri's reaction to the accusations against the famous painter". Akharin Khabar.

- "Laleh Sabouri confirms the sexual assault accusations against Aydin Aghdashloo". MovieMag.ir.

- Fassihi, Farnaz; Porter, Catherine (November 2, 2020). "Famed Iranian Artist Under #MeToo Cloud Faces Art World Repercussions". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

- "Style Talk, Meet Tara Aghdashloo". Les Belles Heures. June 1, 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

my own father Aydin Aghdashloo,

- "An Interview With Abbas Kiarostami and Aydin Aghdashloo". Offscreen, Volume 21 Issue 7. July 2017. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

Takin, my son!

- "Shohreh Aghdashloo Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved November 2, 2020.

Lucie-Smith, Edward (September 1999). Art Today. Phaidon Press. ISBN 0-7148-3888-8.

External links

- Aydin Aghdashloo's Official Website

- Ali Dehbāshi, Aghdashloo, a passer-by by the side of the wall (Aghdashloo, āberi dar kenār-e divār), in Persian, Jadid Online, January 30, 2009, .

• Aghdashloo: Living to Paint, in English, Jadid Online, May 14, 2009, .

• Audio slideshow by Shokā Sahrā'i, in Persian (with English subtitles), Jadid Online, 2009: (7 min 6 sec).

На других языках

- [en] Aydin Aghdashloo

[es] Aydin Aghdashloo

Aydin Aghdashloo (en idioma persa: آیدین آغداشلو ) nacido el 30 de octubre de 1940, es un pintor, diseñador gráfico, escritor y crítico de cine iraní,[1] y uno de los mejores -artistas conocidos- del arte moderno y arte contemporáneo de Irán. Sus obras de arte son conocidas por mostrar el pensamiento de muerte gradual y desgracia, y también por recrear trabajos clásicos notables de forma moderna y surrealista. Sus dos series de Recuperaciones de Terminación y Años de Fuego y Nieve son consideradas parte de la serie más importante del arte iraní moderno.[ru] Агдашлу, Айдын

Айдын Агдашлу (род. 30 октября 1940, Решт) — иранский художник, график, писатель, кинокритик. Агдашло был награждён французским правительством кавалером (рыцарем) за свои гражданские заслуги.Другой контент может иметь иную лицензию. Перед использованием материалов сайта WikiSort.org внимательно изучите правила лицензирования конкретных элементов наполнения сайта.

WikiSort.org - проект по пересортировке и дополнению контента Википедии